Italiensk futurisme og fortiden som besvær

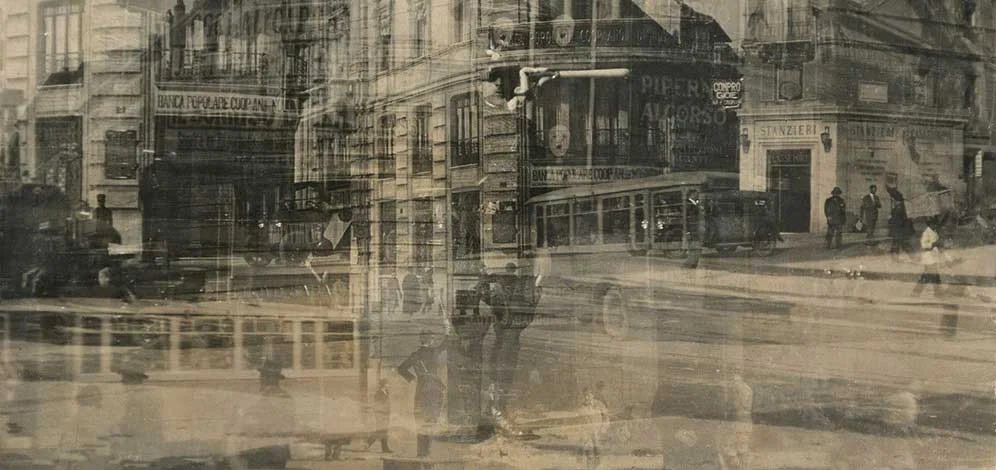

Mario Bellusi, Traffico moderno nell’antica Roma, 1930. © Museo d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, Trento.

(Scroll down for English version)

Italia på begynnelsen av 1900-tallet var et land av kontraster, og futurismen, den italienske avantgarde i samtida, skulle vise seg å være like kontrastfylt. Futurismen slik den ble lansert av Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) i manifestet fra 1909 var opprinnelig en litterær bevegelse, men utviklet seg raskt til å bli noe mer enn det – futurismen ble en livsstil, med et antall manifester å vise til.

Futuristene var unge, moderne og opprørske; disipler av den moderne, industrielle og urbane by. De samlet seg i en «maskinens kult», tok til orde for krig, og mot et bakteppe av økonomisk, kulturell og sosial endring gikk futuristene i fortropp for det nye Italia. Men denne grådigheten for fremtiden var ledsaget av et hat mot fortiden. De så et Italia bundet i arvens lenker og som urørlig lå underlagt tradisjon, de så et land i identitetskrise som skyldig måtte vende seg tilbake mot fortiden. Og Roma, med lite utviklet industri, tynget av både byråkrati og pavekirke, var selve kroneksemplet på den døde by. Futuristene kjente denne vekten av fortiden som kreativt kneblende og handlingslammende for nasjonen. Ved å la seg inspirere av selve kjennetegnene på moderniteten – den industrielle byen, urbanitet, maskiner, elektrisitet og fart– skulle de skape en ny og revitalisert estetikk for en ny tid, og et Italia de igjen kunne være stolte av. I The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism erklærer Marinetti:

We affirm that the beauty of the world has been enriched by a new form of beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car with a hood that glistens with large pipes resembling a serpent with explosive breath . . . a roaring automobile that seems to ride on grapeshot—that is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

Å kalle en bil skjønnere enn en av verdens mest anerkjente antikke skulpturer vitner om futuristenes dristige og aggressive opprør mot det klassiske og tradisjonsbundne – mot skillet mellom kunst og forbruksvare – og er bare en av mange beskrivelser av deres håp om estetisk herredømme. Og hva er vel ikke mer perverst enn det ytrede ønske om å slå selv seiersgudinnen Nike? Men futuristene var også politisk engasjerte, og mye av den volden de tar til orde for i de mange manifestene kommer til uttrykk i gatebildet. På et tidspunkt dannet også futuristene et politisk parti, og selv om dette var kortlivet er det ingen tvil om at kunst og politikk ligger tett opp mot hverandre i futurismen. Det må dermed påpekes at dette gjør det vanskelig å skille de fra hverandre.

Nike fra Samothrake, 220-190 f.v.t. © Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Hvordan forholder futurismen seg egentlig til tradisjonen og fortiden? Bevegelsen representerer den merkelige, nærmest paradoksale sammenblandingen av nasjonalisme og forakt for fortiden. Men er futurismens forhold til modernasjonens fortid helt uproblematisk? Er de unge italienerne egentlig modige nok til å tenne fyrstikken, brenne alle broer og stå helt alene i en «brave new world»? Denne teksten vil hevde at også futurismen lider av et komplekst forhold til fortiden, og vil i denne sammenheng undersøke måten Roma fungerer som symbol på fortiden, og hva dette symbolet således inneholder for futuristene. Men også Roma slik byen som sted fremkommer helt spesifikt representert i billedlige verker er viktig i denne sammenheng. Kanskje finner vi også i futurismen noe som vitner om angsten for å kutte navlestrengen?

Futurismen og avantgarden

Da Marinetti snakket om en «earth shrunk by speed» satte han ord på en ny tid karakterisert av industrialisering, masseproduksjon, raske biler, raskere tog og enda raskere fly. I en tid der alt gikk raskere ønsket Marinetti et formspråk som representerte møtet med denne nye verden, for med samfunnets ytre transformasjoner fulgte nødvendigvis også menneskets nye opplevelse av verden. Futurismen kan kanskje karakteriseres som en dehumanisering av kunsten, som en stadig artikulert fremtidsutopi der «The suffering of a man is of the same interest to us as the suffering of an electric lamp …». Denne formen for likestilling mellom mann og maskin kaster kanskje et foruroligende lys over futuristenes oppvigleri til krig, men mer generelt sier det noe om futuristenes syn på mennesket, og mennesket som fremstilt i kunsten.

Det futuristiske formspråkets arv lå i divisjonisme, den italienske ekvivalenten til franskmennenes pointillisme. Divisjonisme er en teknikk der ublandede farger påføres lerretet i små avgrensede områder, og som på avstand gir en optisk effekt av sterke, unike farger. I samme manifest som sammenlikningen ovenfor er hentet fra, erklærte de futuristiske malerne også at «painting cannot exist without divisionism», og klarte således på egenhånd å understreke historisk kontinuitet og arven fra en bevegelse som gjerne forbindes med en alternerende realistisk og symbolistisk vinkling i bildene. Videre proklamerer futuristene at denne divisjonismen «must be an innate complementariness», noe Christine Poggi kommenterer som en fortsatt tro på kunstnergeniet og hans evne til å velge farger som reflekterer en gjenstands indre liv. Ved å støte fra seg alt som smaker av naturalisme, perspektiv og menneskelig dominans i handlingsrommet, velger futuristene å behandle farger symbolsk. Det følger at futuristene dermed ikke bare anser de levende og de dødes følelsesliv som jevnbyrdig, men understreker samtidig viktigheten av kunstneren – også i den moderne verden – som en fortolker av forholdet mellom mann og maskin. Har futuristen, tilsynelatende ved å neglisjere menneskets indre liv, likevel vist seg å være en skap-romantiker?

Mer treffende kan vi kanskje se futurismen som nok en avantgarde-bevegelse ved begynnelsen av det nye århundret som tar opp i seg og spiller på de samme karaktertrekkene som har vært formgivende for moderne og avantgardistisk kunst helt siden Baudelaire. Blant annet står myten om kunstnergeniet fremdeles sterkt også i denne myten om moderniteten. Men også futuristenes eksperimenter med synestesier, dvs. sammenblandede sanseerfaringer, kan spores tilbake til Baudelaire, blant annet slik det fremkommer i diktet Correspondances: «There are perfumes as cool as the flesh of children». Liknende skriver Carlo Carrà (1881-1966) i «The Painting of Sounds, Noises, and Smells» at «there are sounds, noises, and smells which are concave, convex, triangular, ellipsoidal, oblong, conical, spherical, spiral, etc.» Baudelaire er også mannen som i 1846 fremla visjonen om en ny kunst for en ny tid; en kunst der motivene skulle søkes i og fremvise en erfaring av nettopp samtiden. I et slikt aspekt kan futurismen sees på som et naturlig uttrykk for en kontinuitet innenfor en tradisjon som har sitt omdreiningspunkt i spørsmålet om nettopp modernitet. I et slikt perspektiv synes futurismen kun en av mange bevegelser som ønsker å besvare spørsmålet om hva det egentlig vil si å være moderne.

Umberto Boccioni, La città che sale, 1910-11. © The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Giacomo Ballas (1871-1958) Lampada ad arco (1910-1911) vitner om en slik kontinuitet, og kan kanskje karakteriseres som et overgangsverk mellom den eldre divisjonistiske garde og den unge futuristiske fortropp. Sammenliknet med The Worker’s Day fra 1904 ser vi tydelig hvordan fremstillingen av lyset endrer seg hos Balla i denne overgangen. I 1904 er Balla opptatt av det naturlige lyset, og selv om vi ser en lykt som skinner også her, er dette bildet dominert av det naturlige skumringslyset. I 1911 har maktforholdet mellom lykten og månen blitt snudd på hodet. Her feirer Balla elektrisitetens seier over månelyset – en ny, menneskeskapt og kunstig verden. Mer eksplisitt er dette et bilde på modernitetens seier over det romantiske, et konsept som for Marinetti er tydelig forbundet med femininitet og tradisjonell kunst, og dermed erklært foraktelig allerede i det første manifestet. I 1911 drukner månen i den voldsomme energien som Ballas lykt uttrykker, noe som blant annet skyldes at de divisjonistiske «flekkene» har blitt omgjort til V-formede lyspiler. Månen som symbol på fortiden blir også en allegori på futurismens fiende i en kamp som nærmest når kosmiske dimensjoner i «Let’s Murder the Moonlight!», også skrevet av Marinetti i 1909.

Den spesifikke lykten fant Balla på Piazza Termini i Roma. Lykten som symbol på moderne fremskritt og seier over tradisjonen får ved denne stedsspesifiseringen en tilleggsdimensjon. Om vi husker uttalelsen om å sidestille menneskets og lampens følelser, synes lykten nå også som bildet på den futuristiske gjenopplivningen av den døde byen Roma. Ved å omfavne moderne teknologi skal futurismen lik Dr. Frankenstein igjen blåse liv i en by der samtiden lider under stusselige kår. Eller som Marinetti uttalte i 1909: «We intend to free this nation from its fetid cancer of professors, archaeologists, tour guides, and antiquarians … We intend to liberate it from the countless museums that have covered it like so many cemeteries.» Sitatet vitner også om at vi til tross for futuristenes fokus på det vitenskapelige og teknologiske stadig finner spor av en også mystisk slagside.

Et nytt perspektiv

Futurismen var opprinnelig Norditaliensk, men på midten av 1920-tallet flyttet futurismen hovedsete fra Milano til Roma. Dette var også en periode med utskiftninger innenfor bevegelsen; nye kunstnere slapp til og futuristene utviklet både nye metoder og motiver. Maskinene hadde blitt en del av hverdagen, og futuristenes fremste motiv fra denne perioden blir flyet. Flyets appell lå i den teknologiske nyvinningen og i dets ledende rolle innenfor krigføring. Futuristene drømte om italiensk erobring av luftrommet, og den nye formen for maleri som utviklet seg i perioden – Aeropittura – tok utgangspunkt i nettopp denne idéen om dominans. Aeropittura knyttet flyet og kameraet sammen i kunsten, slik som de to også var tett knytt sammen innenfor krigføringsstrategi. Futuristenes idé om krig var tett forbundet med tanken om tilblivelse og hygiene, om de unges kamp mot de eldre. For futuristene går alt stadig fortere, og maskinene synes en naturlig forlengelse av menneskekroppen – flyvemaskinen synes en naturlig protese. Emily Braun skriver om de futuristiske Aeropitture:

The sweeping, panoramic image of the ground below, a favored composition of aeropittura, deliberatley emulated the panoptic gaze of the divine. Mechanized flight realized age-old mythologies of attaining the heavens, and the bomber, like God, now had the power to decide the life or death of those below.

Tullio Crali, Granvolta Rovesciata [Giro della morte], 1938. © Collection of Luce Marinetti, Roma.

Objektet fly og opplevelsen å fly er likevel to forskjellige ting. Mens mange futurister var opptatte av å avbilde selve flyvemaskinen i aksjon på himmelen, er Tullio Crali (1910-2000) i motsetning til dem kanskje den som kommer nærmest billedliggjøringen av selve opplevelsen. Han tok utgangspunkt i det nye perspektivet som flyvingen innebar. I Granvolta Rovesciata [Giro della morte] (1938) ser vi taket på en by, muligens Roma, presse seg mot oss. Betrakteren får virkelig følelsen av farten og trykket som oppstår under flyvingen, og det kjennes nesten som vi skal streife borti spirene på kirkene. Bildet fremviser både den potensielle maktdominans som ligger i flyet og den virkelige muligheten for en endret verden under vingene på en mutert menneske-maskin. For i dette bildet ser vi en helt ny måte å tenke maleri på, og parallelt med dette også visjonen om en helt ny verden.

Flyets skygge minner heller ikke bemerkelsesverdig lite om korsets skygge. Dette hadde også forfatteren og politikeren D’Annunzio lagt merke til, og han understreket videre at de begge påkaller tanken om offer og frelse. Vi ser dermed at futuristenes ønske om samfunnsomveltning får en ny dimensjon så fort flyet blir en del av estetikken, perspektivet og språket: nå sammenlikner futuristene seg også med Gud. I 1931 publiseres «Manifesto of Futurist Sacred Art», en totalomvending for futuristene som i de tidligere årene hadde sett kristendommen som det største hinderet i arbeidet med å kutte kontakten med fortiden. De erklærte i 1910: «The god of this new religion is Industrial Greatness, and the second-in-command, Brute Force». Men nå, etter at den første bølgen med futurisme har lagt seg, oppstår altså en vilje til å vende tilbake til Italias katolske røtter, og vi ser i kunsten en mystisk fusjonering av teknologi og kristendom.

Ikke besynderlig er det også i denne perioden fascismen virkelig får fotfeste i italiensk politikk. Futurismen som siden begynnelsen har vært opptatt av nasjonen, Italias identitet, krig og vold er nå utrolig vanskelig å skille fra fascismen. Samtidig blir også grensen mellom kunsten og politikken, mellom kunsten og livet vanskelig å trekke opp. Den futuristiske maleren og fotografen Tato (1896-1974) var en av dem som så futurismen som det endelige kunstneriske uttrykket for Mussolinis Tredje Roma, og avbildet blant annet i en gave til Føreren fascistenes marsj mot Roma. I Tatos Sorvolando in spirale il Colosseo (Spiralata) (1930) er det to tydelige fokuseringspunkt: Colosseum og flyet. Colosseum, Roma og den imperialske fortiden ligger der nede, mens der oppe ser vi flyet, det moderne Roma. Spiralen flyet har etterlatt seg i luften gir gjenlyd i Colosseums spiralform. Tato trekker opp direkte forbindelseslinjer mellom fascistenes nye rike og det gamle Romerriket, og bruker Colosseum som symbol akkurat som Mussolini selv hadde gjort. Denne formen for futurisme har nesten gått opp i en fascistisk trope, for på mange måter er dette bare billedliggjøringen av Via dei Fori Imperiali. På bakgrunn av slike bilder kan vi kanskje spørre oss om ikke futuristene her har gått på kompromiss med sitt tidligere seg fordi en sterkere makt har gjort seg synlig i gatebildet? Har futuristene blitt veike? Har de begynt å lengte tilbake?

Men igjen kan vi jo også, som journalisten og litteraturkritikeren Giuseppe Prezzolini (1882-1982), argumentere for forskjellene på fascismen og futurismen. Prezzolini mener de to ikke kan sameksistere. Han skriver:

Fascism, if I am not mistaken, wants hierarchy, tradition, and observance of authority. Fascism is content when it invokes Rome and the classical past. Fascism wants to stay within the lines of thought that have been traced by the great Italians and the great Italian institutions, including Catholicism. Futurism, instead, is quite the opposite of this. Futurism is a protest against tradition; it’s a struggle against museums, classicism, and scholastic honors.

Kanskje er Tatos bilde et av få futuristiske verk der fascisme og futurisme synes å gå opp i opp. I andre tilfeller er det hele mer komplekst, også i andre av Tatos bilder. Han var blant annet kjent som en eksperimenterende og nyskapende fotograf som ertet på seg de konservative. Han arbeidet dessuten også med metoder som kan sammenliknes med både Dada og Surrealismens. Det må i tillegg nevnes at dette er mannen som i 1920 arrangerte sin egen begravelse slik at han kunne bli gjenfødt som den futuristiske kunstneren Tato. Denne opprørske, fryktløse og anti-tradisjonelle siden av Tato fikk sine etterfølgere særlig i fotografiet. På liknende måte som Tato i Il perfetto borghese (The Perfect Bourgeois) (1930) bytter ut ansiktet på denne herremannen med en kleshenger, fjerner Mario Bellusi (1891-1955) i Traffico moderno nell’antica Roma (Modern Traffic in Ancient Rome) (1930), alt som kan minne om det antikke Roma. Bildet består av flere negativer lagt over hverandre slik at spøkelsesaktige figurer synes å tre frem, som fra et sted inne i bildet. Bildet får et uttrykk av noe hjemsøkende, kanskje slik futuristene opplevde at Roma stadig var hjemsøkt av sin fortid?

Noe liknende kan vi også se i Filippo Masoeros (1894-1969) fotografier der han under akrobatiske flyvninger over Roma har tatt bilder av kjente monumenter. Masoeros arbeider karakteriseres av fart, og gjennom bruk av både flyet og kameraet fremviser bildene hans et Roma vi aldri før har sett. I fotografiene hans oppstår en ny virkelighet som er fjern fra virkeligheten slik vi kjenner den. Kun monumentene forblir gjenkjennelige da alt annet er gjort uklart. Og igjen trekkes vi mot fortiden, men denne gangen trekkes vi gjennom fremtiden. Således kan vi kanskje til slutt spørre oss om futuristene egentlig klarte, selv om de stadig presset gasspedalen hardere, å råkjøre vekk fra fortiden?

English version

Future’s Past: Italian Futurism and the Struggle of Historical Continuity

Italy in the beginning of the 20th century was a country of contrasts, and futurism, the Italian avant-garde at the time, was to be just as contradictory. Futurism as it was launched by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) in the manifesto of 1909 was from the beginning a literary movement, but quickly developed into something more – futurism became a way of life, with a number of manifestos to match. The futurists were young, modern and rebellious; disciples of the modern, industrial and urban city. They gathered in a “cult of the machine», spoke of war, and against a backdrop of economic, cultural and social change the futurists saw themselves as the vanguard of the new Italy. But this greediness for the future went hand in hand with a hatred directed at the past. They saw an Italy bound by the chains of the past, a country subject to tradition. They saw a country in a deep state of identity crisis that guiltily had to look to the past. And Rome, with little developed industry, made heavy by both bureaucracy and the papal state, was in their eyes the prime example of the dead city. The futurists felt this weight of the past as both creatively disabling and paralysing of the nation. Getting inspired by the very characteristics of modernity – the industrial city, urbanization, machines, electricity and speed – they wanted to create a new and revitalized aesthetic fit for a new age, and an Italy they again could be proud of. In The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism Marinetti declares:

We affirm that the beauty of the world has been enriched by a new form of beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car with a hood that glistens with large pipes resembling a serpent with explosive breath . . . a roaring automobile that seems to ride on grapeshot—that is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

To call a car more beautiful than one of the worlds most renowned antique sculptures bears proof of the futurists bold and aggressive rebellion against the classical and traditionbound – against the boundaries between art and consumables – and it is only one of many descriptions of their hope of aesthetic subjugation. Also, one could ask, what is more perverse than the goal of defeating even Nike, the goddess of victory? The futurists were politically engaged as well, and much of the violence they are advocating in their manifestos comes to life in the streets. At one point the futurists also formed a political party, and even though it was short-lived, it leaves no doubt that art and politics is tightly interwoven in the futurist movement. It should therefore be noted that these two often becomes hard to separate.

How does futurism really relate to tradition and the past? The movement represents the odd, nearly paradoxical mixing of nationalism and despise of the past. But is futurisms relation to the past of its mother nation really that unproblematic? Are the young Italians really brave enough to light the match, burn all bridges, and stand all alone in a “brave new world”? This paper makes the claim that futurism too, is suffering from a complex relation to the past, and will in this context examine in what way Rome functions as a symbol of the past, and in turn what the futurists put into this symbol. But also, the city of Rome more specifically as represented in futurist works of art will be important in this context. Maybe we can detect even in the futurist movement a sense of anxiety concerning the cutting of the umbilical cord?

Futurism and the avant-garde

When Marinetti wrote of an «earth shrunk by speed» he put to words the sense of a new era characterized by industrialization, mass production, fast cars, faster trains and even faster airplanes. In a time when everything seems to be going faster, Marinetti wished for a mode of expression that represented the encounter with this new world. Because the society had gone through a major external transformation, the human experience of it had changed as well. Futurism may be characterized as a dehumanization of the arts, as an ever pronounced utopia where «The suffering of a man is of the same interest to us as the suffering of an electric lamp …». This form of equality between man and machine may throw a disruptive light on the futurist incitement to war, but more generally, it says something about how the futurists viewed human life, and humans as represented in art.

The futurist mode of expression had its legacy in divisionism, the Italian equivalent of the French pointillism. Divisionism is a technique where unmixed colours are applied to the canvas in small, demarcated spots, so that when seen from afar, it becomes an optic illusion of strong, unique colours. In the same manifesto as the comparison above, the futurist painters declared that «painting cannot exist without divisionism», and managed by this to stress historical continuity and the inherence of a movement that often is associated with alternately realist and symbolic approach to the subject at hand. Further, the futurist proclaim that this form of divisionism «must be an innate complementariness», something that Christine Poggi comments on as a still belief in the artist genius and his ability to choose colours that reflect the inner life of an object. By rejecting everything that tastes of naturalism, perspective and human dominion of the pictorial space, the futurists choose to treat colour symbolically. It follows that the futurists don’t just view the inner life of the alive and the dead as equal, but also emphasize the importance of the artist – even in this modern world – as an interpreter of the relation between man and machine. Has the futurist, by apparently neglecting the inner life of human beings, still managed to come through as a closet-romantic?

More aptly we may view futurism as yet another avant-garde movement at the beginning of the new century that adopts and uses the same characteristics that have shaped modern and avant-garde art ever since Baudelaire. Among other things, the myth of the artist genius is still central also in this myth of modernity. But the futurist experiments with synaesthesia, which is blended sensory experiences, can also be traced back to Baudelaire. In his poem Correspondances we read: «There are perfumes as cool as the flesh of children». Similarly Carlo Carrà (1881-1966) writes in «The Painting of Sounds, Noises, and Smells» that «there are sounds, noises, and smells which are concave, convex, triangular, ellipsoidal, oblong, conical, spherical, spiral, etc.» Baudelaire is the same guy who in 1846 presented his vision of a new art fit for a new era; an art where the subjects were to be found in the contemporary society, as well as expose an experience due to this encounter. In this way futurism can been viewed as a natural expression of continuity within a tradition that centres on the question of modernity. In such a perspective futurism may seem just one of many movements that seeks an answer to the question of what it really means to be modern.

Giacomo Ballas (1871-1958) Lampada ad arco (1910-1911) bears witness to this kind of continuity, and we may call this piece a transitional work where the elder divisionism meets the young futurist vanguard. Compared to The Worker’s Day of 1904 we can clearly see how the representation of light changes as the artist finds himself in this transition. In 1904 Ballas main concern seems to be the natural light, and even though we do detect a streetlamp burning also in this picture, it still is the twilight that is dominating. In 1911 the power relation of the streetlight and the moon has changed. Now Balla seems to be celebrating the victory of electricity on behalf of the moonlight – a new, manmade and artificial world. More explicitly is this a picture of modernity’s triumph over the notion of the romantic, a concept that for Marinetti is tightly connected to femininity and traditional forms of art, and thus declared despicable already in the first futurist manifesto. The moon seems to drown in the intense energy expressed by Ballas lamp, owing to among other things the fact that Balla exchanged the divisionist spots with V-shaped arrows of light. The moon as a symbol of the past also becomes an allegory on the futurist enemy, in a battle that reaches nearly cosmic dimensions in «Let’s Murder the Moonlight!», written by Marinetti i 1909.

The specific streetlamp Balla found in the Piazza Termini in Rome. The lamp as a symbol of modern progress and triumph over tradition has now by this mentioning of an actual place got an additional dimension. Recalling the wish to equate the feelings of man and lamp, the lamp now becomes a picture of the futurist resurrection of the dead city of Rome. By embracing modern technology, futurism will, just like Doctor Frankenstein, breath life back into a city were the contemporary suffers under bad conditions. Or as Marinetti wrote in 1909: «We intend to free this nation from its fetid cancer of professors, archaeologists, tour guides, and antiquarians … We intend to liberate it from the countless museums that have covered it like so many cemeteries.» Furthermore, this bears witness to the fact that we, in spite of the futurist focus on science and technology, still find traces of something mystical.

A new perspective

Futurism was originally north Italian, but in the mid-1920s futurism moved from Milan to Rome. This was also a time of change within the movement itself; new artists came to and the futurists developed both new methods and motifs. Machines were now a part of everyday life, and the main futurist subject of this period is to be the airplane. The airplane’s appeal was its technological innovation and its leading role in the art of warfare. The futurists dreamt of Italian conquest of the heavens, and the new mode of painting that develops during this period – Aeropittura – was based on this exact idea of domination. Aeropittura tied the airplane and the camera together in the arts, just as it was tightly tied together in military intelligence and strategy. The futurists notion of war was closely linked to the idea of becoming and hygiene, of the young’s struggle against the old. To the futurists everything is always moving faster, and the machine seems a natural extension of the human body – the airplane a natural prosthesis. Emily Braun writes of the futurist Aeropitture:

The sweeping, panoramic image of the ground below, a favored composition of aeropittura, deliberatley emulated the panoptic gaze of the divine. Mechanized flight realized age-old mythologies of attaining the heavens, and the bomber, like God, now had the power to decide the life or death of those below.

The object airplane and the experience to fly are certainly two different things. While many futurists were concerned with depicting the actual airplane in action, Tullio Crali (1910-2000) has a different approach to the subject matter. He is probably the futurist closest to illustrating the experience of flying. He based his work on the new perspective made available by flight. In Granvolta Rovesciata [Giro della morte] (1938) we see the city roof, possibly Rome, thrust itself against us. The viewer really gets the sense of speed and pressure that occurs during flight, and it feels almost as if we are going to touch the church spires. The picture is showing both the potential power-dominance of the airplane and the real possibility of a changed world under the wings of this morphed man-machine. In this painting we see a wholly new way of thinking painting, parallel with the vision of a new world.

The shadow of the airplane is also reminiscent of the shadow of the cross. This was detected by the author and politician D’Annunzio as well, who noted that they both evoke the idea of sacrifice and salvation. Thus we notice that the futurist wish for revolution got an additional dimension once the airplane became part of the aesthetic, perspective and language: the futurists now compare themselves to God. In 1931 the «Manifesto of Futurist Sacred Art» is published, a reversal of prior futurist declarations. In the earlier years the futurists had viewed Christianity as the key opponent in their struggle to cut all ties to the past. In 1910 they declared: «The god of this new religion is Industrial Greatness, and the second-in-command, Brute Force». But now, as the first wave of futurism fades away, there arose a will to once more turn back to Italy’s catholic legacy, and in the art of the period we notice the mystical fusion of technology and Christianity.

Not surprisingly, this is also the time when fascism really gets a hold in Italian politics. The futurist movement that ever since it was launched had been preoccupied with the nation, the identity of Italy, war and violence, now becomes almost inseparable from fascism. This distinction between art and politics, between art and life, now seems hard to draw. The futurist painter and photographer Tato (1896-1974) became one of those who saw futurism as the ultimate artistic expression of Mussolinis Third Rome, and among other things he depicted the fascist march on Rome as a gift for the leader himself. In Tatos Sorvolando in spirale il Colosseo (Spiralata) (1930) there are two main focal points: The Colosseum and the airplane. The Colosseum, Rome and the imperial past lies down below, while up in the air we notice the airplane and modern Rome. The spiral the plane has left behind echoes the spiral shaped Colosseum. Tato is drawing up direct lines of connection between the new fascist kingdom and the old Roman Empire, and he uses as his main symbol the Colosseum just as Mussolini himself had done. This form of futurism has almost dissolved into a fascist trope, because in many ways this painting is merely the visual equivalent of the Via dei Fori Imperiali. Based on such paintings we may ask ourselves if the futurists are compromising their former self because a stronger power now has taken to the streets? Have the futurist become weak? Have they started to yearn for the past?

At the same time, we might also argue that fascism and futurism is contradictory, just as the journalist and literary critic Giuseppe Prezzolini (1882-1982) had done. He writes:

Fascism, if I am not mistaken, wants hierarchy, tradition, and observance of authority. Fascism is content when it invokes Rome and the classical past. Fascism wants to stay within the lines of thought that have been traced by the great Italians and the great Italian institutions, including Catholicism. Futurism, instead, is quite the opposite of this. Futurism is a protest against tradition; it’s a struggle against museums, classicism, and scholastic honors.

Maybe Tatos painting is just one of the few futurist pictures where fascism and futurism seems one and the same. In other cases, things appear more complex, as is also the case with other pictures by Tato. He was renowned as an experimenting and innovative photographer who mocked the conservatives. He also worked with methods that can be compared to both Dada and Surrealist modes of creation. It is also worth mentioning that this is the same guy who in 1920 arranged his own funeral in order to be resurrected as the futurist painter Tato. This rebellious, fearless and anti-traditional side of him got many followers, especially in photography. Just as Tato in i Il perfetto borghese (The Perfect Bourgeois) (1930) swaps the face of this gentleman with that of a clothing hanger, Mario Bellusi (1891-1955) in Traffico moderno nell’antica Roma (Modern Traffic in Ancient Rome) (1930) removes everything that reminds of the ancient Rome. The picture consists of multiple negatives laid on top of each other so that ghostly figures emerges, from somewhere inside the picture it seems. The picture thus gets the expression of something haunting, maybe in the same way that the futurists felt Rome to be ever haunted by its past?

Something similar may be noticed in Filippo Masoeros (1894-1969) photographs in which he during acrobatic flights across Rome took photos of famous monuments. Masoeros works is characterized by speed, and using both the airplane and the camera, we see in his photos a Rome we have never seen before. A new reality seems to come to life in his photos, a reality very distant from reality as we know it. Only the monuments remain recognizable when everything is blurred out. And once more we find ourselves drawn towards the past, but this time we are drawn through the future. Thus, we may finally ask ourselves if the futurist really did manage, even though the kept pressing the accelerator ever harder, to speed away from the past?

Bibliografi:

Baudelaire, Charles. «Correspondances». Oversatt av William Aggeler. Hentet fra https://fleursdumal.org/poem/103. 08.11.18

Boccioni, Umberto, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla og Gino Severini. «Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto». I Futurism: an anthology, redigert av Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi og Laura Wittman, 64-67. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Braun, Emily. «Shock and Awe: Futurist Aeropittura and the Theories of Giulio Douhet». I Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe, redigert av Vivien Greene, 269-273. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2014.

Carrà, Carlo. «The Painting of Sounds, Noises, and Smells». I Futurism: an anthology, redigert av Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi og Laura Wittman, 155-159. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Chu, Petra ten-Doesschate. Nineteenth-Century European Art. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Person Education, 2012

Fraquelli, Simonetta. «Modified Divisionism: Futurist Painting in 1910». I Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe, redigert av Vivien Greene, 79-82. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2014.

Gentile, Emilio. «The Reign of the Man Whose Roots are Cut: Dehumanism and Anti-Christianity in the Futurist Revolution». I Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe, redigert av Vivien Greene, 170-172. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2014.

Greene, Vivien. «Introduction». I Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe, redigert av Vivien Greene, 21. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2014.

Lyttleton, Adrian. «Futurism, Politics, and Society». I Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe, redigert av Vivien Greene, 58-76. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2014.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. «Destruction of Syntax – Radio Imagination – Words-in-freedom». I Futurism: an anthology, redigert av Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi og Laura Wittman, 143-151. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. «Let’s Murder the Moonlight!». I Futurism: an anthology, redigert av Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi og Laura Wittman, 54-61. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso. «The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism». I Futurism: an anthology, redigert av Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi og Laura Wittman, 49-53. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Mobilio, Albert. «A Zoom with a View: Tullio Crali’s Death Loop», Hyperallergic. Publisert 23.08.14. Lest 08.11.18. https://hyperallergic.com/145119/a-zoom-with-a-view-tullio-cralis-death-loop/

Mørstad, Erik. «Divisjonisme», i Malerileksikon. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, 2007.

Nevinson, Margaret Wynne. «Futurism and Woman». I Futurism: an anthology, redigert av Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi og Laura Wittman, 74-75. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Pelizzari, Maria Antonella. «Futurist Photography: Tato and the 1930s». I Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe, redigert av Vivien Greene, 295-299. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2014.

Salaris, Claudia. «The Invention of the Programmatic Avant-Garde». I Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe, redigert av Vivien Greene, 22-49. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2014.

![Tullio Crali, Granvolta Rovesciata [Giro della morte], 1938. © Collection of Luce Marinetti, Roma.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c45cad2ee17599e0bf51197/1560437075549-42JSNZ5P8WDJW3ATSYRZ/Ill.+9.jpg)