Living Things. Picasso Figure / Still-Life

This show assembles sketches, studies, prints and paintings that reveal some of the ways in which Picasso began to transform figures into objects and objects into figures, opening his work to metamorphosis from 1907 onwards.

Picasso first experimented with metamorphosis in 1907, when he began to transform the objects he depicted, converting figures into objects and vice versa, and creating new objects that were also figures.

The exhibition is a selection of paintings, prints, studies and sketches that show how the trend materialised in Picasso's oeuvre during his Cubist period and then between 1924 and the early thirties, years in which he met and worked closely with the Surrealists.

The exhibition is called Living Objects because Picasso's transpositions between figures and objects enliven the inanimate. Heads are at once guitars, still lifes become automata and objects behave as if they were actors on the stage, or else are blown to smithereens like the defenceless victims.

Tree figure (1907 - 1908)

Alongside the Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907, Picasso made flowing studies of trees in landscapes. The linear rhythms developed in them are almost interchangeable with those present in a series of figure studies leading to major figure paintings in 1907-8. Trees can become bodies.

Transformations (1913 - 1914)

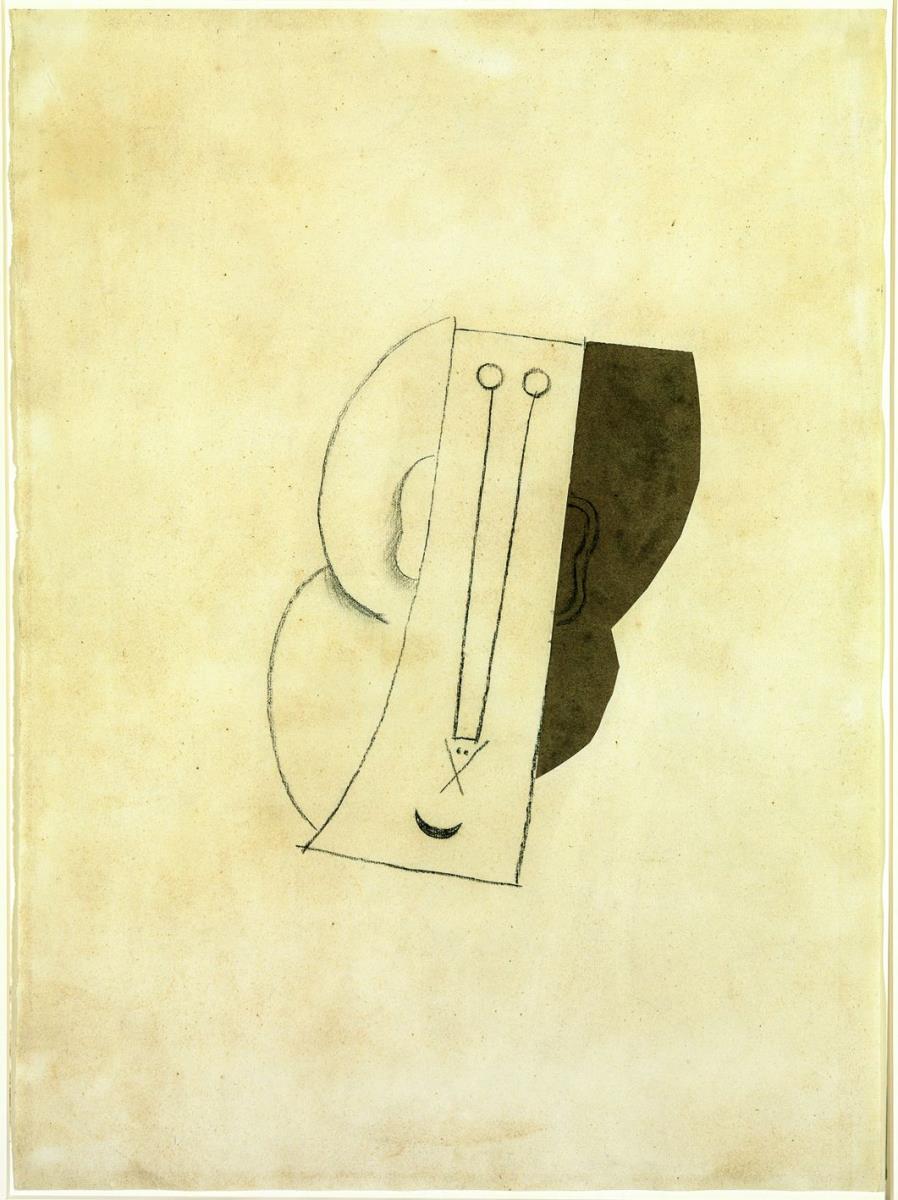

In 1912-13, Picasso invented a new, very simple pictorial vocabulary. His signs for musical instruments and heads were now so easily exchanged that his heads are visibly on the way to or from being musical instruments.

Transformations (1915 - 1916)

In 1915, Picasso painted a series of watercolour and gouache still lives in several of which fruit-bowls with long necks form the heads in arrangements where clarinets and the arms of stringed instruments reach outwards from table-tops like gesticulating limbs. In the same year, he painted a flat yet monumental Harlequin whose long neck and tiny circular head reappear in a more intimate still-life as the neck and top of a bottle of Anis del Mono. The lozenge pattern of the bottle echoes harlequin’s costume, and the harlequin-bottle with its grey shadow rock away from the vertical as if they are dance partners.

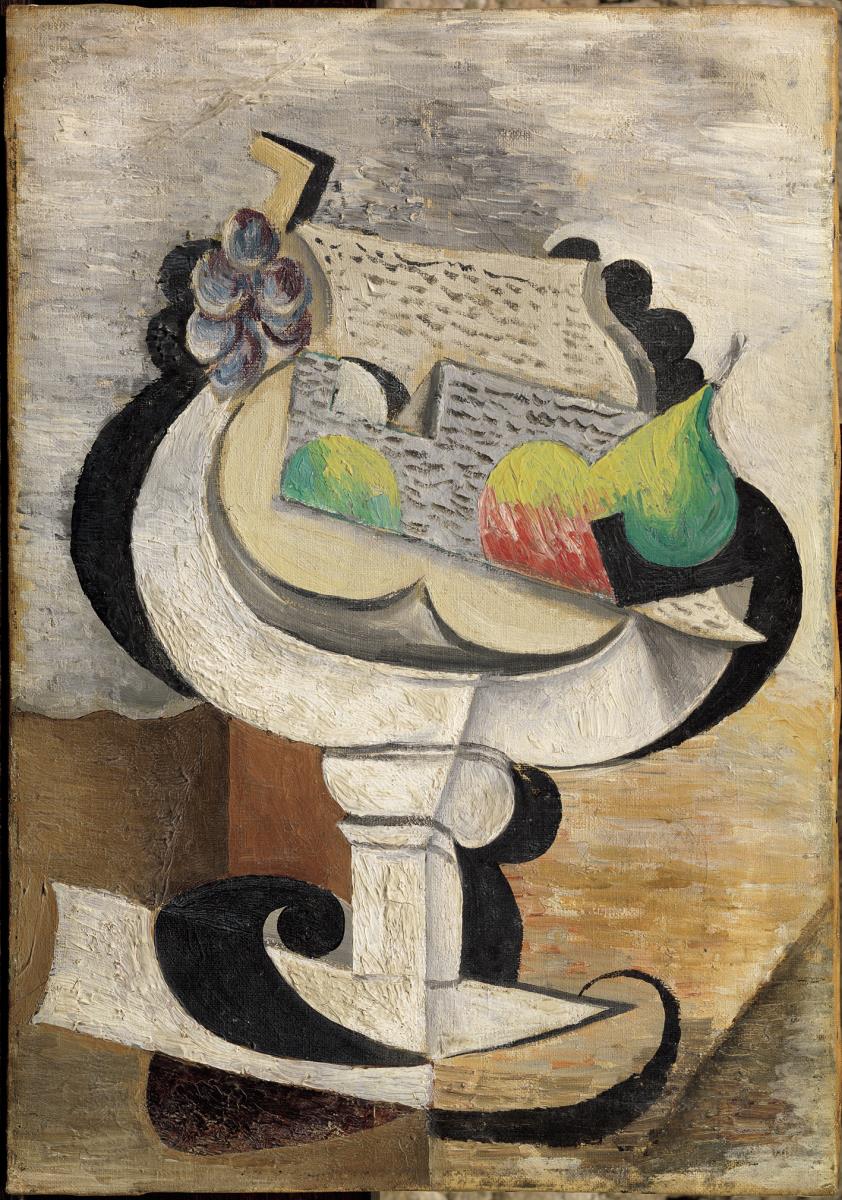

Transformations (1917 - 1920)

By 1917, the pedestal-table still-life had appeared in Picasso’s work. Its attraction was the ease with which objects, table-tops and table legs could be seen as figures: living furniture. By 1920 Picasso was returning to the pedestal-table still-life repeatedly, working in different media to produce variation after variation, often animating his still-lives in such a way that they become jaunty musicians.

Repeating patterns

With the simplification of his signs came an overlap in Picasso’s work between representing things and pattern making. In 1922 this led to a suite of still-lives that emphasize their repeated use of pattern by employing combinations of stripes and checks. These both explore the room for variation where elements and even groupings of signs are repeated, and test the threshold between abstraction and representation where signs are abstracted almost beyond legibility. Picasso followed these up in 1924 with extensive suites of drawings, mostly in sketchbooks, using almost exclusively dots and lines.

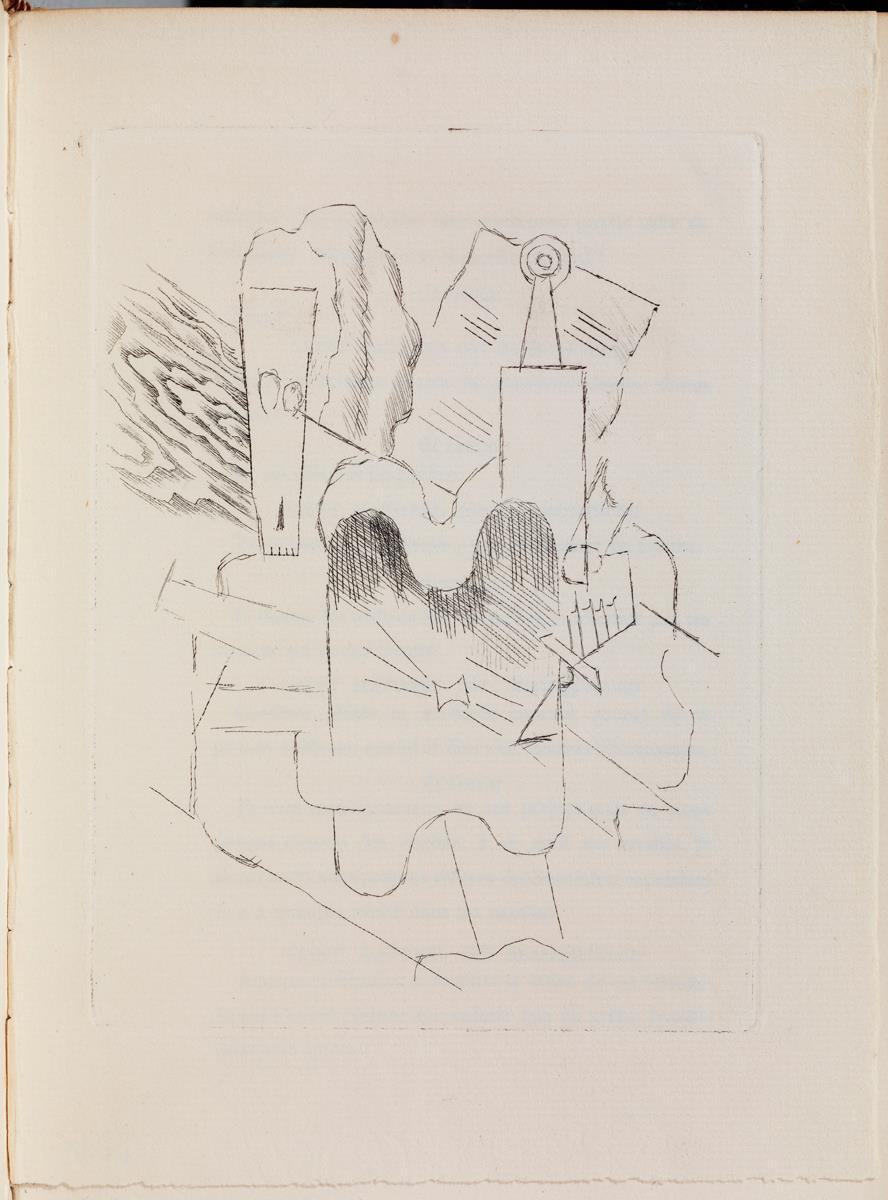

Picasso's sketch books (1924 - 1925)

This space contains images digitized from sketchbooks filled by Picasso in 1924-25. One group of sketches uses only a very simple dot-and-line technique which Picasso took from diagrams of constellations. A second group are sketches for the drop curtain of the ballet Mercure, which was performed in June 1924 and provided a theatrical spring-board for new still-life paintings. A third group are ideas for the tableau ‘Night’ in the ballet – a reclining figure in front of a starry sky – and for the tableau of ‘the Three Graces’. In a fourth group Picasso tries out different combinations of still-life objects alongside the major still-life paintings of 1924-25.

The ballet Mercure (1924)

Picasso’s thirteen tableaux for the ballet Mercure were his response to Comte Etienne de Beaumont’s request that he work freely with the “alphabet” of gods, humans and beasts and supplied by Greek and Roman mythology. The music was by Erik Satie, the lighting by Loie Fuller, and the ballet was performed in a Montmartre music hall, the Théâtre de la Cigale. Flimsy assemblages were combined with performers taking up “plastic poses” in a series of scenes, no longer than a minute each. The surrealists greeted the production with applause for Picasso.

The theatre of still-life

Alongside his work for the ballet Mercure and afterwards on the Mediterranean at Juan-les-Pins, Picasso painted a series of still-lives where a restricted dramatis personae of objects (musical instruments, bottles and bowls) are presented like actors on stage-like tables, often in front of outdoor backdrops.

Monstrous objects (1924 - 1926)

In 1924-26 Picasso increasingly used the still-life theme to introduce a more violent eroticism into his painting by giving organic form to things and laying them out like body parts which he cut by scratching his lines into the wet paint. These still-lives accompanied the violent eroticism of figure paintings that explicitly bring together love and death.