Jack Brabham, Repco engineer Nigel Tait, and Brabham BT19 Repco. Sandown Park Melbourne for its Tasman Series debut, January 1966. RB620 ‘E2’ engine in 2.5 litre capacity. (Australian Post magazine)

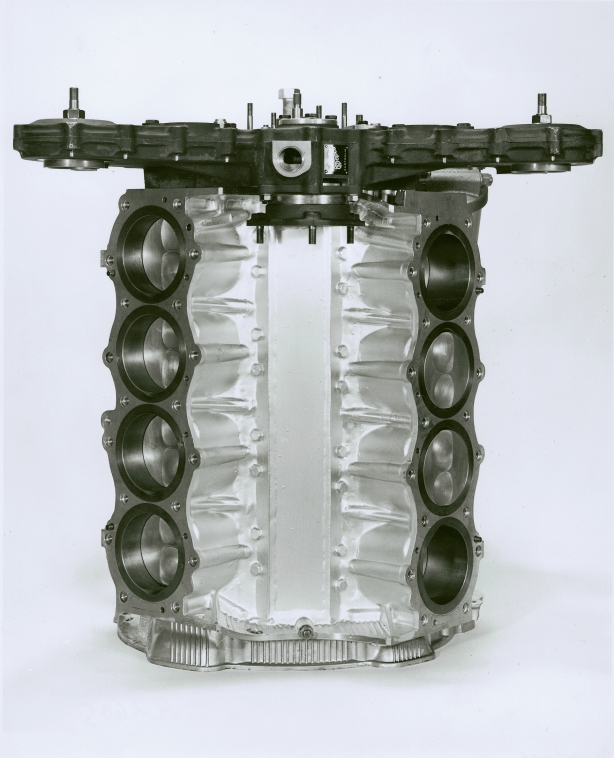

Repco Brabham ‘RB 620 Series’ 3 litre SOHC V8 engine. The ’66 World Championship winning engine. Circa 310 bhp @ 8000 rpm. Weight 160 Kg, the ‘600 series’ block was F85 Oldsmobile based, ’20 series’ heads early crossflow type (Repco)

In this Repco article we start with a summary of the events leading to Repco’s involvement in Grand Prix Racing, then identify key team members, the equipment used to build the engines and finally have a detailed account of the 1966 championship winning engines construction…

Why did Repco Commit to Grand Prix Racing?…

Younger readers may not know the background to Australian automotive company, Repco’s involvement in Grand Prix racing in the mid-sixties.

Coventry Climax, the Cosworth Engineering of their day caused chaos for British GP teams when they announced they would not build an engine for the new 3 litre F1 commencing in 1966.

Repco had serviced the 2.5 litre Coventry Climax FPF four cylinder engines, the engine ‘de jour’ in local Tasman races, but were looking for an alternative to protect their competitive position, Jack Brabham suggested a production based V8 to them.

Brabham identified an alloy, linerless V8 GM Oldsmobile engine, a project which had been abandoned by them due to production costs. Jack pitched the notion of racing engines of 2.5 litre and 3 litre displacements using simple, chain driven SOHC, two valve heads to Repco’s CEO Charles McGrath.

GM developed a family of engines comprising the F85 Oldsmobile and Buick 215. They were almost identical except that the F85 variant had six head studs per cylinder rather than the five of the 215 and was therefore Brabham’s preferred competition option.

Jack had first seen the engines potential racing against Chuck Daigh’s Scarab Buick RE Intercontinental Formula mid-engined single seater in a one off appearance by Lance Reventlow’s outfit at Sandown, Australia, in early 1962.

The engine’s competition credentials were further established at Indianapolis that year when Indy debutant Dan Gurney qualified Mickey Thomson’s 215 engined car eighth, the car failing with transmission problems after 92 laps. It was the first appearance of a stock block engined car at Indy since 1945.

Jack Brabham looking carefully at the Buick 3.9 litre engine in the mid-engined Scarab RE at Sandown Park, Melbourne in 1962, filing the information away for future reference! (Doug Nye with Jack Brabham)

Whilst the engine choice was not a ‘sure thing’ its competition potential was clear to Brabham, as astute as he was practical.

At the time the engine was the lightest mass production V8 in the world with a dry weight of 144 kg and compact external dimensions to boot. Its future at GM ended in 1963 due to high production costs and wastage rates on imperfectly cast blocks, about 400,000 engines had been built by that time.

New Kid on the Block…

‘Having talked my way into the Repco Brabham Engine Co with a promise of hard work and a 3 weeks trial I was very happy’ recalls Rodway Wolfe.

I was given a nice grey dustcoat with a lovely Repco Brabham insignia on the pocket and shown around the factory and introduced to everyone- I was the seventh employee. Repco had picked the cream of their machinists from throughout the empire to work at RBE, they were great guys to work with and willing to share all their skills.

The three-week trial period was a gimmick, after a few days I had settled in as one of the team. After the trial my wage was increased to slightly higher than my previous job in the Repco merchandising company.’

People: Key Team Members…

L>R: Phil Irving, Bob Brown, Frank Hallam and Peter Holinger dyno testing the first 2.5 litre Tasman RB620 engine at Russell Manufacturing’s engine test lab in Richmond in March 1965. Weber carbs borrowed from Bib Stillwell, the engine did not race in this form. The engine initially produced 235 bhp @ 8200 rpm, equivalent to a 2.5 Coventry Climax engine. ‘Ciggies a wonderful period touch (Repco)

The first prototype RB engine was built at the Repco Engine Laboratory in Richmond, Victoria, an inner Melbourne suburb, then a hub of manufacturing now a desirable inner city place to live, 1.5 km from the CBD.

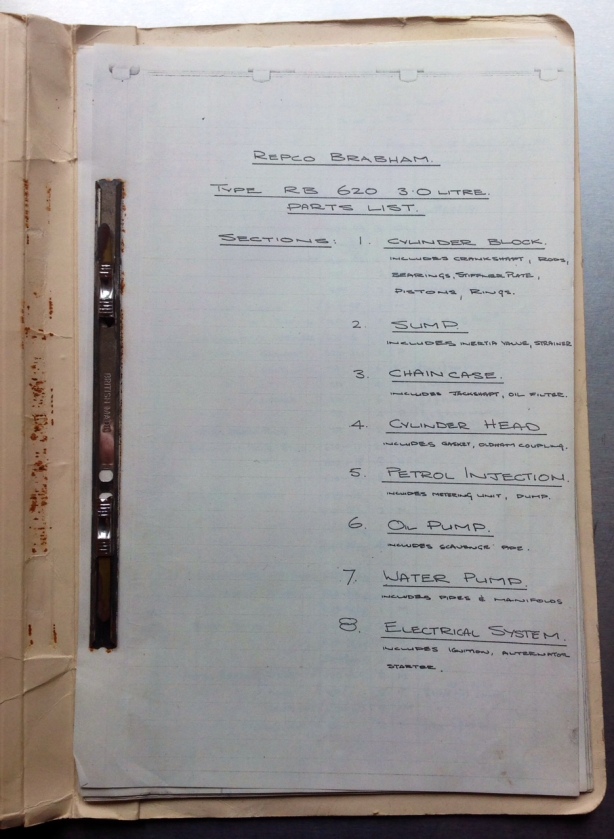

It was designated the type ‘RB620’, which was the nex file number of the various laboratory, research and development projects in process at the time.

‘Frank Hallam was General Manager and Phil Irving was Project Engineer together with Nigel Tait and others. Peter Holinger made the components and Michael Gasking tested the engines. There were others involved before my time, those mentioned were involved at Richmond’.

As an industrial site using steel garages in Richmond the RB project received comment in various overseas publications as the ‘World Championship Fl engine built in a tin shed in Australia’.

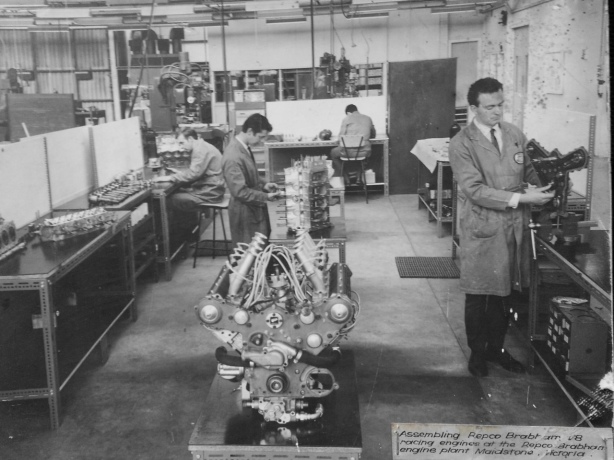

When I joined in late 1965 the project had just arrived at the Maidstone, Melbourne factory. (87 Mitchell Street, Maidstone, then an industrial Melbourne western suburb, 10 km from the CBD) The Manager was Frank Hallam. In the drawing office, the Chief Engineer was Phil Irving, the Production Manager Peter Holinger, Production Superintendent Kevin Davies and the machine shop leading hand was David Nash. We also had a Commercial Manager, Stan Johnson who came and went’.

Frank Hallam and Jack Brabham discuss the turning of camshaft blanks on the Tovaglieri lathe (Repco)

‘Around this time Michael Gasking also transferred from the Richmond Laboratory- he was Chief of Engine Assembly and Testing. Also on the machine tools was John Mepstead who was a great all rounder and later appointed to help Michael with engine assembly. He eventually joined Frank Matich to ‘spanner’ the 1969 Australian Sports Car Championship winning Matich SR4 Repco.

Frank Hallam arranged for me to attend RMIT night school, Repco picked up the bill. Those Tuesday and Thursday nights for 4 years helped me immensely, over the period I obtained a certificate in ‘Capstan and Turret and Automatic Screw Machines’ operation and a certificate in ‘Product Drafting’. My status was as a First Class Machinist in the Repco Brabham factory.

If I had any queries I would also ask Phil Irving who loved a yarn and was a huge bank of knowledge. I felt so honoured to to work for him, and learned so much’.

‘Repco Record’, the internal Repco staff magazine announces the formation of Repco Brabham Engines Pty. Ltd. (Repco)

Machine Tools…

‘Frank Hallam was a machine tool enthusiast.

It was a big help, he made sure we worshipped our machines, blowing away the swarf with an air hose. I learned respect and cleanliness of all machine tools. Few machine shops were as clean or free of swarf and mess everywhere with the exception of Holinger Engineering, Peter was also fastidious.

We were lucky to have top machines in the workshop. Our biggest was an Ikegai horizontal boring machine. RBE had two lathes- a Dean Smith & Grace English machine and also a Tovaglieri Italian unit.

We had a small Deckel horizontal borer and a couple of mills- a Bridgeport and a French Vernier. The older machine was a Herbert capstan lathe, I used this to make every stud for all the future Repco Brabham engines- main bearing and cylinder head studs, a very big variety in different steel types, it was repetitive stuff that would normally be boring but I didn’t care, we were winning the World Championship’…

‘When he drew a new design of stud, Phil Irving would come out and check my thoughts on being able to make it with what we had and other various things. We would do a yield point test in a vice where we measured the length of the new stud after I made a sample and then tension it to a nominated foot pound tension and we would keep increasing the tension until the stud refused to return to the original length. That tension was known as the yield point so Phil would pick a tension somewhere in a safe range under that yield point’.

RB620 Series Engine: Machining and Modification of the Oldsmobile F85 block…

Not the sharpest of shots but a rare one showing the ‘production’ Olds and RB620 engines. RB620 on the right. The engine was the lightest production V8 in the world at the time (unattributed)

‘When I arrived there were a lot of aluminum cylinder blocks along one factory wall. Repco acquired twenty-six Oldsmobile cylinder blocks from General Motors in the US. (2 of the 26 were prototype engines E1 and E2 which were built up in Richmond)

One of my first jobs was to remove all the piston assemblies from those twenty-four blocks. They were not short blocks as known in Australia (here they are complete without sump or cylinder heads) but these were not complete to that stage. They had crank bearings in place, all main bearing caps and the 3.5 inch liners were cast into the block. We didn’t use the cast iron main bearing caps or bolts, replacing them with steel caps and high strength studs.

The RB 620 used the original 3.5 inch cast in sleeves but practically everything else was changed.

All surfaces were re-machined for accuracy, all bolt thread holes re-tapped and recessed to accept studs of superior material. The camshaft bearings were in the valley of the block of course but we pressed them out and rotated them 45 degrees and pressed them back in place to cut off the original oil galleries as our engine ran twin overhead camshafts, one per cylinder bank.

The front original camshaft bearing was left intact and the second camshaft bearing was removed and fitted was a sleeve with an INA roller bearing.

We made up little jackshafts which were driven from the crankshaft by a duplex chain, which also drove the single row chain driving the overhead camshafts. These jackshafts used the first original Oldsmobile slipper bearing and a small roller type bearing in the second original cam bearing location. The chains etc, were all enclosed inside the RB chain-case.

RB600 F85 Olds block from above. Note the valley cover of aluminium sealed ‘with a sea of Araldite then painted over with Silverfros- those blocks which are still in service today still retain the Araldited plate and still do not leak’ comments ex RBE engineer Nigel Tait. Phil Irving’s design had lots of clever bits including the timing chain arrangement which allowed the heads to be removed in the field without disturbing the engine timing- and was also clever in that the same head could be used on either side of the engine (Tait/Repco)

‘A lot of people in 1966, including the international motoring writers, did not realise the extent of the machining required to the F85 Oldsmobile cylinder block to use as our race engine base. It was more work and and involved to adapt the F85 than in machining our new Repco cast blocks (700 and 800 Series) used later in the project.

It used to annoy all of us when our engine was referred to as ‘based on a Buick’ in various world motoring magazines. It also added insult to injury by them adding ‘Built in a tin shed in Australia’!

We then had to close up the large cavity in the valley where there used to be a cover plate, pushrods and cam followers in the original engine.

We spent many hours fettling aluminum plates by hand and fitting them into the valleys to cover the original cam followers and holes etc. When we had a very good fit of these plates we mixed two pot resin (Araldite) with additional aluminum powder and filled up the valley seams around the plate.

Then with some elaborate heating systems we invented, we dried the Araldite in place. This also gained us the reputation of the ‘The Grand Prix engine held together with Araldite’ in various magazine articles!’

RB600 block on the left, Olds’ F85 unmodified block on the right. The 600 block has the pushrod holes covered with the Araldited aluminium plate. ‘The 1/4 inch thick block stiffener plate protrudes from the top of the modified block. This gives the effect of cross bolting…note also the Repco designed magnesium sump’ notes Tait (Tait/Repco)

‘I finished the job of dismantling the blocks, we only worked on two or three at a time during the early months of 1966. Unless the parts were an easy item or required substantial machine set up we only made a few of each component as design changes were ongoing. Not critical large changes but small subtle ones’.

‘We didn’t have any problems with the Oldsmobile block by there was one race in 1966 when a cylinder liner failed. As explained, we used the cast in liners and retained the 3.5 inch bore.

BRO, (Brabham Racing Organisation) sent back the failed engine block and we bored out the remains of the cylinder liner. There was a casting cavity behind the liner which caused the weakness and failure. This was a problem that could not be dealt with without boring out all the liners and fitting sleeves. Otherwise there could be more failures due to bad castings. From that date we used dry liners and eradicated the risk of it occurring again.’

Jack and Phil specified this aluminium plate to add stiffness to the production F85 Olds block, big holes to provide rod clearance obviously. ‘This block would have had dry sleeves which led to considerable blowby problems due to distortion and eventually wet sleeves were specified by Phil Irving’ notes Nigel Tait (Tait/Repco)

UK Components: Crankshaft etc…

Phil Irving completed most of the design of the engine in England, he rented a flat in Clapham in January 1964 close to BRO and together with Jack they settled on a relatively simple single overhead camshaft configuration compatible with the block and fitment into the unused Brabham BT19 spaceframe chassis. This simplen specificaton is what Jack pitched to the Repco board at the projects outlet.

The BT19 frame had remained unused throughout 1965 when the engine for which it was designed, the Flat-16 Coventry Climax FWMW, was not released to Brabham, Lotus and Cooper as planned.

To expedite things in the UK, whilst simultaneously mailing drawings to Australia, Phil commissioned Sterling Metals to cast the heads. Prior to his return to Australia in September 1964, HRG machined an initial batch of six heads, fitting valves and seats to Irving’s specifications.

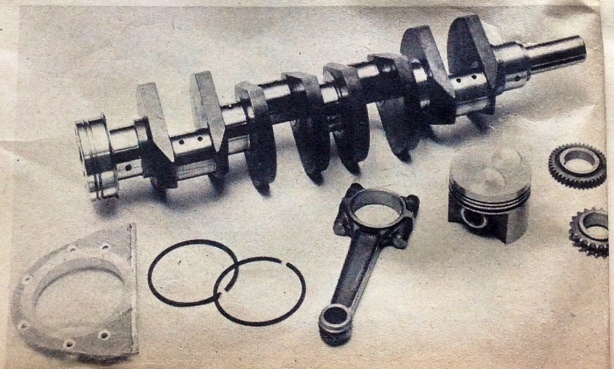

‘Laystall in the UK also made the crankshaft. Constructed from a single steel billet the ‘flat’ nitrided crankshaft was a wonderful Irving design. I don’t recall any updates or changes to the design of the crankshaft over the years the RB engines were built. It was supplied in 2.5, 3 litre and 4.2 litres for the Indy engines- also 4.4, 4.8 and 5 litre sportscar versions. All crankshafts were of the same bearing dimensions etc’.

‘The term ‘flat-crank’ refers to the connecting rod journals being opposite each other and not in multi-plane configuration as is usual in production V8’s. It meant the engine was not such a well balanced unit at low revolutions but it actually converted the engine to virtually two four cylinder units and either cylinder bank would run quite smoothly on its own. The layout also enabled the superior use of exhaust configuration eliminating the need for crossover exhaust pipes to obtain full extraction effect’.

Crankshaft was made by Laystall to Phil Irving’s design, pistons and rings by Repco subsidiaries. (Repco)

Pistons…

‘Repco is a piston ring manufacturer and very experienced in ring design which meant that we were well ahead in that regard.

The famous SS55 oil rings were well known already around the world. The pistons were Repco Products.

No other F1 engine constructor of the sixties made their own pistons. The experience we gained with the supply of Coventry Climax pistons and rings contributed to this success.’

Bearings: Vandervell Interlopers and ‘Racing Improves the Breed’…

‘Repco was already supplying engine bearings to various manufacturers globally from the Tasmanian based Repco Bearing Company, we obtained these components as required.

During 1966 an advert appeared in a British motoring magazine, ‘French Grand Prix won on Vandervell bearings’. Vandervell are of course a British bearing company, Repco were furious and telex messages to and from BRO (Brabham Racing Organization) revealed that Jack Brabham was not happy with the depth of the lead overlay on our copper/lead crankshaft bearings.

Our bearings had a lead overlay of .001 inch and the Vandervell bearings an overlay of .0005. So I was instructed to pack away all our existing bearings and mark them not for use, our bearing company came up with the improved design bearings with the lesser overlay in time for the next GP. Racing certainly improves the product!

Before I transferred to the RB project, i worked in Repco merchandising and received brochures and information about a new Repco alumina/tin bearing known as the ‘Alutin’ and advertised by Repco as a new high performance product. Repco were promoting them as a breakthrough design.

I learned these new bearings had been unsatisfactory under test in the F1 engine and within a short period no more was said about the new product ‘Alutin’. They were inclined to ‘pick up’ on the journals at high rpm – another example of how racing improves the product. This problem had not been evident in the engine testing of the product by Repco to that date.’

Outsourced Items…

‘There were some components we did source outside the Repco Group.

There were cam followers, Alfa Romeo cam buckets, valve springs from W&S, valves manufactured by local company Dreadnaught. The ignition system was sourced from Bosch by Brabham.

The collets were from the UK and were a production car or motorcycle collet, the name escapes me. We made the valve spring retainers and collet retaining caps. Over the project we made changes to the collet retainer material from aluminum to heat treated aluminium bar and later titanium. Not a lot was gained as titanium fatigues as well, as we found out.’

Lucas Fuel Injection…

‘The fuel injectors and fuel distributor were Lucas items, the system was in early stages of development. It consisted of an injector for each cylinder, in our case installed in the inlet trumpet a short distance from the inlet port in the cylinder head.

The system is timed with a fuel distributor in the engine valley driven from the chaincase by the distributor drive gear. The fuel is supplied at 100psi from an electric pump. The fuel pressure supplies and operates small shuttles which are constantly metering supply according to the length of shuttle travel. The amount of fuel supplied to the injectors is controlled by a variable small steel cam which is profiled to suit the particular engine size etc. The steel cam therefore controls the actual fuel mixture and is linked to the throttle inlet slides’.

‘It is interesting to note that although the fuel distributor can be timed to any position in the engine cycle, injecting at the point of the inlet valve opening or with it closed or wherever, it does not make any important difference in engine performance but as Phil Irving explained to me there is a point of injection that lowers engine performance so therefore the fuel distributor is timed in each installation to avoid the undesirable point of injection. The air inlet trumpets were cut to length spun and profiled.

The chaincase was a magnesium casting and the ‘620’ 1966 World Championship engine used a single row handmade chain imported from Morse in the US. We cut all the sprockets and manufactured all the camshaft couplings etc. We used an SCD hydraulic chain adjuster, a standard BMC component.

The cam chain was driven by a small jackshaft which was fitted in the front two original camshaft bearing spaces of the original Olds block. The jackshaft was driven by a Morse duplex chain from the crankshaft sprocket, also Repco made. The crankshaft had a small gear driving the oil pump mounted underneath the chain case.’

Oil Pump…

‘The oil pump was a wonderful Irving design, simple to service but a small work of art. It featured flexible supply hoses with snap fittings and was a combination of oil supply pump which supplied the engine with oil up through a gallery in the chaincase and also a slightly larger scavenge pump connected to each end of the engine sump- it was also a magnesium casting. The pump assemblies, sump and all components were made by Repco.

The system consisted of a sump with an inertia valve located in its lowest point. If the car was braking the inertia moved the valve forward which opened a cavity in the front of the sump causing oil to be drawn from the front. Under acceleration the inertia valve moved backwards and the forward cavity closed and the rear cavity opened. This meant a minimum of blowby and air to be pumped by the scavenge system. I don’t recall any failure of this system apart from the Sandown debut race of our ‘620’ Series 2.5 litre engine in January 1966′.

‘The ‘Tasman’ cars were held on the grid for rather a long time and as a result the oil had cooled in the Repco Brabham. Jack left the line with plenty of revs, the cold oil and resulting oil pressure split the pressure pump gears. The first engines used cast Fordson Major tractor pressure pump gears and one gear had split due to the extreme pressure. Jack Brabham did 3 or 4 laps from memory.

I arrived at work on Monday morning and in typical Irving style found a drawing for the supervisor for the construction of new steel gears and a ‘Do Not Use’ request for all the Fordson gears in stock. Phil had arrived at the drawing office on Sunday evening after the Sandown meeting and made the modifications straight away’.

‘The chaincase featured a couple of inspection caps which were removed to allow for chain tension adjustment etc. We made these caps and when it came to cutting the retaining threads in the chaincase we could not obtain the required thread tap anywhere. Phil had specified similar threads to the Vincent Motorcycle chain adjuster cap threads so that’s exactly what we used. Irving brought in the original Vincent motorcycle thread tap and we used that to thread all the chaincases under manufacture at the time, actually going back to valve spring collet retainer caps.

I recall that the first engines used BSA motorcycle collet retainers. One of the things I enjoyed so much working with Phil was that he did not waste time on risk taking design, he used tried and tested systems from his past. He once said “There is really nothing new, it is just changed around in some way”- well he sure proved that with the first RB620 engine!’

Cylinder Heads…

‘The cylinder heads were cast aluminum of crossflow design, the cam covers cast magnesium. All our cast magnesium and aluminum components were supplied by CAC in Fishermans Bend, Melbourne, with the exception of the first batch of six heads cast in the UK. (Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation).

Phil was remarkable with his engine design skill in that he could see the item in reverse or three dimensions and could design all the sand boxes etc and patterns required to arrive at the finished item.

The engine used no bolts as the original Olds did. Cylinder heads, cam covers, main bearing caps, sump, oil pump and chaincase were fitted with, or retained by high tensile studs.That was my department and apart from the first couple of prototypes I made all the studs for the 1966/67 RB engines. Some were quite a challenge, the thread specification and tolerances were exacting.

The crankshaft rear bearing seal was a slipper ring design with a bolted on ring retaining flange. The slipper rings were supplied by our Russell Manufacturing Co, we made the outer flange in the factory. The steel flywheel was also turned and made by Repco’.

Conncting Rods and Ease of Servicing…

‘We used modified Daimler connecting rods and competition Chevrolet and Repco rods. In later engines we occasionally used Warren rods from the US. In the valley of the engine a small drive housing held the vertical ignition distributor and also the fuel distributor. Sometimes in the larger engines we also fitted a mechanical fuel pump to this housing.’

‘The type 620 engine engine had throttle slides running on small grooves with 1/8 inch steel rollers to prevent lock ups which would be a disaster. The slide covers were fastened directly to the cylinder head and in later engines were changed to fully assembled units and fastened directly to the cylinder heads for ease of changing if required. They were then complete units with studs bolting them to the inlet flanges’.

A big feature of servicing the RB620 engine was that either cylinder head could be removed without disturbing camshaft timing or the camshaft from the cylinder head, a great time saver. (See the photos in the block section above which clearly shows this)

The oil pump can be removed in one small unit and replaced with no other dismantling. Or the two cylinder heads can be removed without disturbing the timing of the camshafts or the chain case. All very important design features for use ‘in the field’.

First Test…

The first engine, a 2.5 litre Tasman engine designated ‘E1’ was fired up on March 26 1965, almost twelve months to the day Phil Irving commenced its design.

It was initially run with Weber 32mm IDM carbs and after a checkover fitted with 40mm Webers. The engine produced 235BHP @ 8200RPM, equivalent to a good Coventry Climax 2.5 FPF at the time.

Repco committed to build 6 engines for the 1966 Tasman Series, later changed to three 2.5 litre Tasman engines and two 3 litre F1 engines, the first race for the new engine was the non-championship South African Grand Prix on January 1 1966, the next part in the Repco story is the 1966 race program for the new engine.

‘2.5 litre 620 V8 E1 on the Heenan and Froude GB4 dynamometer in Cell 4 at Richmond, 1965. The exhausts lead straight out through a hole in the wall. Also there was minimal noise insulation in the tin shed that served as a test cell. Vickers Ruwolt across the road blamed us for the large crack that developed in their brick wall on the other side of Doonside Street!’ recalls Nigel Tait (Tait/Repco)

Photo & Other Credits…

Autocar, ‘Jack Brabhams World Championship Year’, Repco Record, ‘Doug Nye with Jack Brabham’, Australian Post, ‘From Maybach to Repco’ Malcolm Preston, Rodway Wolfe Collection, Nigel Tait recollections and his Collection, Repco Ltd photo archive

Etcetera…

Original RBE Pty.Ltd. Letterhead. Jack Brabham had no financial (equity) or directorship involvement in this company, it was entirely a Repco subsidiary.

‘E1’ was the RB620 prototype Tasman 2.5 litre engine. Most of the entries in this exercise book are dated, this one is not, but its mid 1965, the book records the use of cams with the ‘Wade 185’ grind and the valve timing, no dyno sheets sadly! (Wolfe/Repco)

Have a look at this Repco film produced in mid-1965…

It covers some interesting background on the relationship between Brabham and Repco, footage of Jack at home in the UK, the Brabham factory in New Haw, some on circuit footage at Goodwood and then some sensational coverage of the 1965 Tasman Series in both NZ and Oz. The latter segues nicely into footage of the first ‘RB620’ 2.5 Tasman V8 engine ‘E1’ on the dyno at the Repco Engine Laboratory, at Russell Manufacturing, Richmond in ’65…

Tailpiece: #1-RBE620 2.5 litre ‘E1’, the prototype Tasman 2.5 V8, fitted with Webers on the GB4 dyno- Repco Engine Lab at Russells, Richmond 1965. The box over the Webers is for airflow measurement notes Nigel Tait…

Great stuff Rodway!! Would love to see similar documents based the later 7 and 8 series blocks too, given they were entirely Australian in content.

Stephen, we will be into the ‘740 Series’ engines in the next episode, once we write it! Next 2 or 3 weeks, appreciate the feedback, mark

Simon Oaten, you got it right about ‘A little Australian battler company” The RB620 engine got its name because of Course Repco Brabham but was the 620th small development project in the system. The engine project had a set budget of 10,000 pounds. $20,000 and that was the total that was available to the project and Frank Hallam and Phil Irving managed to come up with the goods.

You share interesting things here. I think that your

blog can go viral easily, but you must give it initial boost and i know how to

do it, just type in google for – wcnu traffic increase

thankyou for showing this amazing Aussie history. A little australian battler company – that took on the world and WON ! awesome

thanks for the feedback Simon, the Repco articles are very popular, we will upload one in the next week which covers Jacks’ 1966 Championship Winning season

Simon Oaten, you got it right about ‘A little Australian battler company” The RB620 engine got its name because of Course Repco Brabham but was the 620th small development project in the system. The engine project had a set budget of 10,000 pounds. $20,000 and that was the total that was available to the project and Frank Hallam and Phil Irving managed to come up with the goods.

My father Graeme ((Rabbit) Bartils is pictured assembling an RB620 in early 1966. I believe he filled in the text book for the cam settings. He is still building cars in Dahlonega, GA, USA.

He went from Repco, Brabham, McLaren, moved into Indycars, GT cars, NASCAR, and them opened his own shop building every 935 Porsche in the US, land speed record cars and many many Hot Rods for some of the biggest names in the business.

Truely one of the “unknown “ aussies legends leading the world with his engineering and fabrication abilities.

Great to hear from you Jeff.

And as you say, an unsung hero, I’ve just keyed ‘Graeme Bartils’ Engines into Google and there are enough references there to keep me going for a while!

So many of the RBE alumni went on to make a difference around the world, clearly your dad is one of them Jeff.

Mark

[…] motorom Australian Repca, Brabham se vratio na pobjedničku stazu s četiri pobjede i ponovnim osvajanjem svjetskog […]

[…] Regular readers will know we have covered the history of these achievements in some detail in previous posts; this one about the ‘RB620 series’ 1966 Championship winning engine…https://primotipo.com/2014/08/07/rb620-v8-building-the-1966-world-championship-winning-engine-rodways… […]

[…] https://primotipo.com/2014/08/07/rb620-v8-building-the-1966-world-championship-winning-engine-rodways… […]

Can you please tell me what foundry casted the engine block and who were the pattern makers?

Hi Jerry,

The Oldsmobile F85 block was cast by GM subsidiary Saginaw Metal Casting Operations, in Saginaw Michigan. I’ve no ideas who made the patterns, also within GM presumably.

Mark

An article on Phil Irving would be great

Cheers Rob, I’ve got one coming up but focussed on the relationship between he and Frank Hallam and the latters attempt to shaft Phil and his Repco legacy after his death. I’m afraid nothing I can write comes close to Irving’s autobiography which is a ‘must have’ book, enjoy the ‘105’! Mark

Hi all at Primotipo.

Your articles on Repco are excellent and I look forward

to your post on Phil Irving ..he was the man.

Referring to the 4.4 620 I have a pair of heads to cams and bits

The heads etc had to be left in Zimbabwe as I had to

Scoot back in 1999.

I have great memories of my time at Maidstone and wish all the best to all the boys who are still with us Gordon.

Thanks Graham, Repco is such a fascinating topic isn’t it, so much was achieved by so few so quickly! I’m happy to take any recollections or comments you may have, input from those who were there is gold. My email address is mark@bisset.com.au, thanks for making contact, Mark

[…] https://primotipo.com/2014/08/07/rb620-v8-building-the-1966-world-championship-winning-engine-rodways… […]

[…] https://primotipo.com/2014/08/07/rb620-v8-building-the-1966-world-championship-winning-engine-rodway… […]

[…] https://primotipo.com/2014/08/07/rb620-v8-building-the-1966-world-championship-winning-engine-rodway… […]

[…] https://primotipo.com/2014/08/07/rb620-v8-building-the-1966-world-championship-winning-engine-rodway… […]

[…] I’ve done this story to death of course, here on the engine; https://primotipo.com/2014/08/07/rb620-v8-building-the-1966-world-championship-winning-engine-rodway… […]

[…] https://primotipo.com/2014/08/07/rb620-v8-building-the-1966-world-championship-winning-engine-rodway… […]

Great article! But, on the picture where you show the “production” Olds next to the Repco engine, You have a picture of an Buick engine, not an Oldsmobile.

Thanks Jarl,

No idea where that shot came from, my understanding is that it was only the number of head studs which differed between the Olds/Buick engines in which case the photo, to show ‘standard’ and ‘race’ engine is still useful.

Mark

I’m trying to find the dimensions of the Cooper rings (Wills rings) that were used to seal the heads of the R-B engines to the blocks. Does anyone here have that information, or contact information to someone who might have some rings on hand?

TRX,

Try posting your question on the ‘Repco Brabham’ Facebook page, there are potentially some follows who may be able to help or point you in the right direction.

Mark

Stumbled across your writing…Thoroughly enjoyed the recall & your research on the RB engine.I distinctly remember the magic sound of this engine, I first heard quiet clearly echoing across the rooftops from down at the Sandown circuit mid 60’s … I was 13 years old and standing out front of my parents home in Dandenong North with neighbor Mr Wagg an English tool maker ,who worked at Repco Dandenong…and him telling me, ” that’s our new racing engine you can hear Chris … it’s a beautiful sound .”

Hi Christopher,

Very much a Sandown local. The whole Repco Brabham Engines program was extraordinary in results- how quickly they came and how little in relative terms was spent.

It’s great that so many of the engines still exist so we can hear that lovely sound of which you made mention, on a regular basis.

Mark

Hi Christopher,

Very much a Sandown local. The whole Repco Brabham Engines program was extraordinary in results- how quickly they came and how little in relative terms was spent.

It’s great that so many of the engines still exist so we can hear that lovely sound of which you made mention, on a regular basis.

Mark

Nicely arranged stuff. I like Primotipo and its articles about Brabham Repco, and other racing makes. Racing in the past century, those were the days. My English is rusty and dead to enable me express all the praise. Luckily, I am able to understand and be immersed in what is written. Thanks.