Buddhism in the art of Takashi Murakami

By Marissa Wong | She/Her/Hers

Takashi Murakami. Photo courtesy of Vogue India.

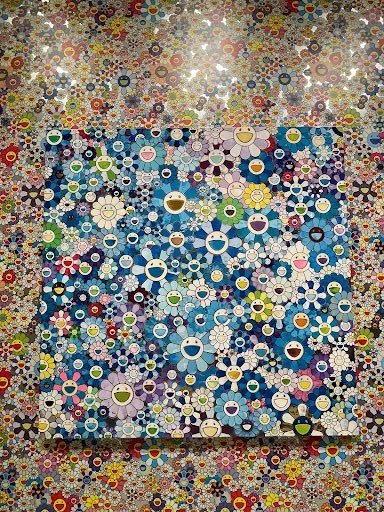

TAKASHI MURAKAMI | KAIKAI KIKI AND ME; AND FLOWER SMILE. Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

I recently visited the special Takashi Murakami exhibit at the Broad Museum in Los Angeles. Murakami is a famous contemporary Japanese artist best known for his colorful smiling flower motifs. His artwork blurs the lines between contemporary Japanese pop culture and more traditional Japanese art, often depicting Buddhism, current social issues, and disasters such as the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami and the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan. Before I went to the Broad exhibit, I knew Murakami as an artist who often collaborated with popular “hypebeast” brands and whose art style is influenced by kawaii and manga culture in Japan, but I did not know how heavily Buddhism influenced many of his works. At first glance at his art, one is immediately struck by his use of vibrant colors and use of “cute” cartoon characters, such as Murakami’s original characters かいかい (kaikai) and きき (kiki), but under the surface of his colorful and bright imagery lies Murakami’s nuanced and complex perspective on humanity, pop culture, the impact of World War II, and the nuclear bombings on Japan.

TAKASHI MURAKAMI | SHANGRI-LA BLUE / SHANGRI-LA PINK, 2012

One piece that was showcased at the Broad was “Shangri-La Blue/ Shangri-La Pink,” 2012. Although the art itself does not appear to have any Buddhist influences, I was struck by the title as I had learned about Shangri-La in reference to Hollywood’s portrayal of Orientalism and Buddhism as an “exotic” and Othered religion, as seen in the 1937 film Lost Horizon.

Shangri-La, as depicted in Capra’s film Lost Horizon (1937)

This film is about Robert Conway, the new Foreign Secretary who has to help rescue Westerners from within a city in China before he can return to the United Kingdom. However, on the plane ride of the last evacuees he escapes with, the plane is hijacked and crashes into the Himalayan mountains. After wandering about the mountains a bit, the group is rescued by Chang and his crew and taken back to Shangri-La, a hidden sanctuary hidden in the Himalayas. Shangri-La is a mystical and exotic place full of knowledge. Robert Conway is enchanted by Shangri-La and does not want to leave, although his group finds the place unnerving and makes plans to escape. Robert meets the High Lama and learns that they did not wind up there by accident, that the residents and founder are extremely old and the founder is looking for someone to keep Shangri-La safe and thriving. Sondra, a woman George meets who grew up in Shangri-La, has read Conway’s books and determined that he was the one to be the successor. Having found Conway, the High Lama peacefully passes away and leaves Robert as the successor. George eventually convinces Robert to leave and he and his girlfriend Maria make arrangements to escape.

The Buddhism portrayed in Lost Horizon (1937) is a magical Tibetan Buddhism that is hidden in the mountains of Tibet in Shangri-La, with a small group of “enlightened” beings untouched by time and by the outside world. Shangri-La is an Orientalist perspective of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism, which controls the West’s idea of what Asia and Buddhism are. Tibet has been “inscribed into the Western Imagination as the place of the sacred and the magical, the last Arcadia on earth: a land of a utopian Shangri-La, white clouds, purest snow, great promise, the most secret places of the earth... etc.” (Whalen-Bridge & Storhoff, p. 54). Geography has played a crucial role in providing a coherent narrative for Western fantasies in the process of recreating the Orient as an “absolute” silent other: “At the core of the imperialist fantasy of Tibet is the mythologization of its landscape- a romanticizing process of the cultural and visual representation of Tibet’s landmark, the Himalayas, invested with and mediated by imperialist ideology” (Whalen-Bridge & Storhoff, p. 54).

In relation to Murakami’s Shangri-La Blue / Shangri-La Pink (2012) artwork, I believe that the title gives a deeper meaning to the surface-level vibrance of the iconic smiling flowers. In Lost Horizon (1937), Shangri-La was depicted as a mysterious and exotic utopia existing outside space and time, mirroring Western notions of Buddhism and romanticizing Shangri-La as an escape for Westerners. It upholds the notion that places like Tibet only exist to serve the unfulfilled desires of the West and that the Orient must cater to the needs of the Occident. While Murakami’s paintings at first appear to simply be a colorful motif of smiling flowers, there is a deeper meaning behind the facade of flowers that serves to remind us of the insidiousness of Orientalism and how Buddhism is often depicted through media.

One of Murakami’s art pieces that contains more overt Buddhist influences is one titled “My arms and legs rot off and though my blood rushes forth, the tranquility of my heart shall be prized above all (Red blood, black blood, blood that is not blood),” pictured below. According to the Broad Museum, “the title of this painting narrates the experience of Daruma, grand patriarch of Zen art and founder of Zen Buddhism. Daruma is famous for sitting in meditation for nine years without blinking while facing the Shaolin Monastery. He lost his arms and legs due to severe atrophy, and even today is a symbol of fortitude and diligence in Japan. This painting is among the earliest direct appearances of Buddhist imagery in Murakami’s work.” Murakami has depicted Daruma several times, varying the color in his series of portraits. In this piece, Daruma and the background are rendered completely black, spotlighting Daruma’s unblinking eyes. Zen Buddhists have long disregarded icons as a means to attaining enlightenment and can be considered iconoclasts. Rather than objects of worship, images such as this portrait can serve as a reminder to Zen practitioners of Daruma’s determination to attain enlightenment through meditation; the spotlight on his large eyes and intense, unwavering gaze recall the legend of the monk cutting off his own eyelids to prevent himself from dozing off during meditation.

TAKASHI MURAKAMI | My arms and legs rot off and though my blood rushes forth, the tranquility of my heart shall be prized above all (Red blood, black blood, blood that is not blood), 2007

The Oval Buddha statue (2008) was also on display at the Broad. In an interview, Murakami described this statue as, “The oval image looks like a Pokemon cuteness character, but he’s sitting on the Shaka Nyorai’s lotus pedestal.” If you look closely at the pedestal, you will notice the lotus flower which the Oval Buddha is perched on. The shape of the pedestal is inspired by a wooden statue of the Shakyamuni Buddha from the 10th or 11th century, who is seated on a large wooden base which is missing some elements, lost over history. Murakami was struck by the unique shape of the pedestal, saying “that piece is broken, but still beautiful.” Oval Buddha silver represents Murakami’s unique ability to combine contemporary Japanese pop culture with historical and Buddhist motifs.

TAKASHI MURAKAMI | Oval Buddha Silver, 2008. Photo courtesy of the Broad Museum.

Murakami began painting arhats in 2009 after being introduced to them by Professor Nobuo Tsuji. In Sanskrit, arhat means “one who is worthy.” An arhat is one who has gained insight into the true nature of existence and has achieved Nirvana, and who chooses to delay their journey to transcendence for the sake of guiding the living toward their own fulfillment. In the wake of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima nuclear disaster, Murakami found that the story of the arhats resonated greatly with him. Murakami once said, “As Buddhism spread from India to China, Korea, and Japan, the religion kept changing as an imported culture. It was revised and fine-tuned along the way, and by the time it reached Japan, it was radically different from the original. The 500 Arhats, for instance, were reinvented here in the context of disease and pandemics: each Arhat, in the Japanese context, was to cure one specific type of ailment.” According to the Broad Museum, “The arhats mediate a wish for the divine, a dream of perfection, with a reality of pain and loss, of work needing to be done, of lives and livelihoods in need of rebuilding. In Murakami’s work, the arhats wear their grotesque features unblinkingly as they haunt a land pummeled by natural disaster and death.” Murakami’s depiction of arhats comes at a time in human existence where natural disasters are commonplace as global warming worsens, global pandemics are becoming more frequent, and the loss of human life has happened on an unimaginable scale. Through the way he depicts arhats as monstrous and grotesque in form, Murakami’s fascination with them shows his acknowledgement of the world we live in but also his hope for the future and for humanity's attainment of enlightenment and an end to the cycle of suffering.

TAKASHI MURAKAMI | 100 Arhats, 2013

Photo courtesy of MCA Chicago

Over his career, Takashi Murakami has excelled at employing vibrant imagery to make powerful statements about many aspects of society, from war and natural disasters to consumerism and waste, often drawing on aspects of contemporary culture from both Japan and the West, such as Harajuku culture. In the past decade, however, by drawing from his cultural roots and the works of past great Japanese artists, Murakami has found a new vocabulary with which to capture the essence of the human condition. In particular, through his multifaceted treatment of traditional Buddhist concepts and themes, Murakami creates contemporary artistic expressions that can help us better understand the human condition and the world we currently inhabit. Although Murakami is only known by some as the artist who collaborates with brands such as Louis Vuitton or as the artist with the wild fashion, his artwork holds much deeper and more significant meaning when you delve below what lays on the surface, and there are many Buddhist teachings and values he draws from that are apparent in his artwork.

References

Whalen-Bridge, J., & Storhoff, G. (2015). Buddhism and American cinema. SUNY Press.