Israel fractures by faith on politics and society

(RNS) Israel today grapples with profound existential questions of its national identity, including how Jewish the Jewish state can be.

More than three-quarters (76%) of Israeli Jews believe their country can be both Jewish and democratic, a view rejected by majorities of Israeli Muslims and Christians, according to a comprehensive new survey released by the Washington-based Pew Research Center Tuesday.

The report also highlights the precarious relationship between Jews and Arabs in Israel, with nearly half (48%) of Jewish Israelis favoring the expulsion or transfer of Arabs — chiefly Muslim — from the nation.

“The survey finds deep religious divisions in Israeli society, not only between Jews and Arabs, but also among Jews,” said Alan Cooperman, director of religion research at Pew.

Among the report’s other findings: While nearly all Israeli Jews say they’re Jewish, half (49%) consider themselves secular, even as they engage in some Jewish religious practices. And one in five Jewish Israelis profess no belief in God.

“Mostly what we find is a huge gulf between ultra-Orthodox and secular Jews,” said Neha Sahgal, a senior researcher on the survey, “Israel’s Religiously Divided Society,” which is based on face-to-face interviews of more than 5,600 Israeli Jews, Muslims, Christians and Druze.

Secular Israeli Jews, for example, say they are more uncomfortable with the idea of their child marrying a very Orthodox Jew than a Christian, the report shows.

On whether Arabs should be allowed to live in the Jewish state, Cooperman said Pew asked the question in general terms because its researchers know of no official Israeli proposal to expel Arabs.

At the same time, “this is an idea that has been raised and bandied around for more than a decade,” he said. “All we can say is that the broad idea of transfer or expulsion has evenly split the Israeli public.”

Israel releases Nazi's plea for clemency

As for Israel’s character, the study found 62% of all Israeli Jews believe that democratic principles should outweigh Jewish law (halakhah) when the two conflict.

But among the “haredim” in Israel, or the most fervently Orthodox Jews, 89% believe that Jewish law should take precedence over democratic principles. The same percentage of secular Jews — or “hilonim” — say democratic principles should trump religious law.

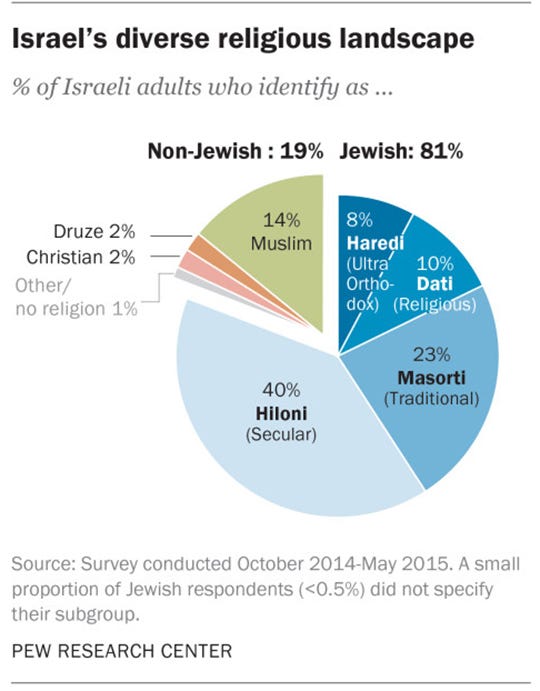

When the question of Israel’s Jewish and democratic character is put to non-Jewish Israelis — who comprise 19% of the Jewish state’s population — 63% of Muslims and 72% of Christians say Israel cannot be both Jewish and democratic.

The report also found some consensus among Jewish Israelis, particularly on the idea of the nation as a sanctuary for Jews. Nearly all (98%) concur that Jews around the world have a right to citizenship in Israel. This belief is linked to another shared by more than 9 in 10 Israeli Jews: that Israel, founded in 1948 in the wake of the Holocaust, is necessary to the long-term survival of the Jewish people.

Pew’s study comes three years after the release of its “Portrait of Jewish Americans,” a survey that shocked many with its finding that most American Jews consider their Judaism rooted more in culture and ancestry than religion.

Taken together, the two Pew reports delve deeply into the beliefs of 80% of the world’s close to 14 million Jews, and invite comparisons between its two largest national communities, which are of roughly equivalent size.

“There are deep bonds between Jews in the two countries,” said Cooperman. Most Israeli Jews (59%), for example, say American Jews have a good influence on the way things are going in Israel.

Netanyahu: U.S., Israel close on military aid package

Religiously, however, American and Israeli Jews show a marked distinction. Orthodox Jews make up about 1 in 5 Israelis, but only 1 in 10 American Jews. And while Israeli Jews are more likely to gravitate toward the extremes — either very or hardly religious — American Jews tend to populate a middle ground, the survey shows.

Higher percentages of Israelis say they go to synagogue weekly, light Sabbath candles and keep kosher. “But there’s also a paradox here,” Cooperman said. “In some ways, Israeli Jews are also less observant than American Jews as a whole.”

The share of Israeli Jews who say they never go to synagogue is higher, for example, 33 versus 22%. And about a third of American Jews (35%) say they attend synagogue “a few times a year, such as for High Holidays,” higher than the 14% of Israeli Jews.

One of the hallmarks of the new study is the breaking down of Israeli Jews into four subgroups, categorizations that can highlight how religious observance correlates with views on a host of pressing societal questions. (These groupings are not analogous to those that describe the various American Jewish approaches to Judaism.)

Between the haredim at one pole (9% of Israeli Jews), and the hilonim (49%) at the other, the survey uses two other categories. The “datim” (13%) are Orthodox Jews who engage far more than the haredim in Israel’s larger society, and the “masortim” (29%) fall between Orthodoxy and secularism.

So on a question about Jewish law and society — for example, should public transportation shut down on Shabbat — responses vary markedly among the four subgroups. While 96% of the haredim favor a shutdown, fewer of the other groups agree — 85% of datim, 44% of masortim and 6% of hilonim.

And as distinct as the responses among Israel’s Jews, a starker contrast divides Jews and Arabs on some of the most fundamental questions of Israeli life.

For example: 42% of Jewish Israelis say the West Bank settlements help Israel’s security and 30% say these Jewish communities — illegal under international law — hurt it. But 29% of Muslim Israelis say they help and 61% say they hurt.

And while 21% of Israeli Jews say there is “a lot of discrimination against Muslims” in Israel, 79% of Israeli Arabs hold that view.

Other findings of the report include:

— About one-third of Jewish men in Israel say they wear a kippa or other head covering that denotes respect for God.

— About half of Israel Jews are Ashkenazi, with ancestral roots in Central or Eastern Europe, and half are Sephardi or Mizrahi, with roots in Spain, the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

— Muslims in Israel are generally more religious than Israeli Jews — nearly 7 in 10 Muslims (68%) say religion is very important in their lives — but less religious than Muslims living in many other countries in the region.

The report, funded in part by the Neubauer Family Foundation, has a margin of error of plus or minus 3% among Israeli Jews, plus or minus 6% among Israeli Muslims, plus or minus 9% among Israeli Christians and plus or minus 11% for Druze in Israel.

(Lauren Markoe is a national reporter for RNS)

This story originally appeared on Religion News Service. Its content was created separately to USA TODAY.