The New York Public Library has abandoned controversial plans to renovate its Fifth Avenue central research branch, a 100-year-old beaux-arts landmark that was set to be converted into a lending library. The NYPL will instead renovate its Mid-Manhattan branch, a large but fairly rundown lending branch across from the research institution.

The move is a substantial and unexpected U-turn for the country’s second-largest library system, which for two years faced concerted protests from employees, library patrons, and architectural preservationists but insisted that its proposals were the only way forward. The Central Library Plan, as it was called, would have blasted open the stacks underneath the research branch’s upper reading room and exiled 1.5m books to a warehouse in New Jersey. Tony Marx, the library’s chief executive officer, had described the plan as one that would “replace books with people.” But many of the city’s researchers and writers, including Junot Diaz, Lydia Davis and Art Spiegelman, demonstrated against the plans – which they called everything from plutocratic to barbarous.

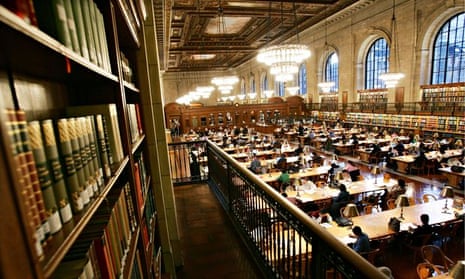

Four different lawsuits had been filed against the project, accusing the library both of endangering its purpose as a research institution and of damaging the architectural integrity of the central branch. In the landmark building, which opened in 1911 and was designed by the eminent architectural firm Carrère and Hastings, the reading room sits unusually at the top of the building, above massive stacks of books that are ferried to readers via a system of centralized elevators. The Central Library Plan would have broken open the stacks to create a lending library, designed by the British firm Foster & Partners, that would have featured sofas and computer banks but would have exiled most of the books to an underground storage facility or an offsite warehouse. (While the library published several schematic renderings, Foster’s full designs have never been revealed to the public.)

The shift is also a victory – if perhaps an accidental one – for Bill de Blasio, the city’s new mayor, who campaigned against the renovations during last year’s municipal election. In his previous role as New York’s public advocate, de Blasio joined demonstrators on the steps of the NYPL to oppose the Central Library Plan. But he had not spoken out on the library plans since taking office on 1 January.

The library is set to receive $150m in public funds when the mayor announces his first budget on Thursday. The cost of the Central Library Plan had been initially estimated at $300m, but that number had increased significantly in recent months as the library reconsidered the costs of renovation.

“I had no idea this was coming, but I never believed it wasn’t possible,” said Caleb Crain, author of the novel Necessary Errors and one of New York’s most consistent critics of the Central Library Plan. In 2012, Crain had advocated for a revised plan that would have retained the central branch as a research library and upgraded the sicklier Mid-Manhattan branch into a major lending institution. The NYPL, at the time, called that idea impossible. It now plans to do almost precisely what Crain proposed.

Much of the angry rhetoric surrounding the Central Library Plan concerned the possibilities of e-books and the supposed eclipse of printed volumes by digital media. But legal, rather than technological, obstacles would have made much of the NYPL’s collection inaccessible. “The vast majority of books were printed between 1923 and today, and every one of those remains in copyright,” said Crain. “For many we can’t make digital copies even if we wanted to. And the fact is that people absorb information better from printed paper than they do from screens. If you’re a researcher, the NYPL and the Library of Congress are the only two major libraries where you can work if you’re not a professor or a student.”

Among the community of writers and researchers who had rallied against the plan, the mood on Wednesday was one of elation mixed with disbelief. “I’m shocked. I never expected we would win,” said Charles Petersen, a senior editor at the magazine n+1. “It seemed like this was something that was very much on the backburner, though we did get the sense that the library’s leadership was uncertain themselves. I think that the big thing is that the research library is going to remain one of the greatest libraries in the world. That’s what it means for me as a writer.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion