1. The overview

The election is the third presidential poll since the fall of the Taliban. It should pave the way for the country's first-ever peaceful democratic transfer of power, because the constitution bars the incumbent, Hamid Karzai, from standing again. The fact that Afghanistan has never managed such a handover before is an indication of how fraught the process could be, even without the complication of a raging insurgency.

Karzai has led the country since the fall of the Taliban. Initially he was appointed by a national assembly, but he went on to win two elections in his own right. The arrival of a new president after more than a decade will shake up the country's tiny elite, although the shifts may not be dramatic if the winning candidate is Karzai's brother or a close ally.

Whoever wins, Karzai will still be living just a stone's throw from the presidential palace, in a property requisitioned from the United Nations and currently under renovation. He is not expected to fade into retirement.

The country's last king was deposed in the early 1970s and only one of the men to lead the country since then has met a natural end. The macabre track record means Karzai will be keen to ensure the elections produce a successor who will not only respect him, but keep him alive. He has reportedly rejected the idea of disappearing to a quiet and luxurious exile, even though he would almost certainly find sponsors.

Karzai is not the only fixture about to vanish from the Afghan political scene. Foreign troops, which have dominated life and politics for over a decade, will also be gone by the start of 2015. The new president will have to rely only on his own police and army to keep the Taliban at bay.

If Karzai decides to sign a long-term security deal with the US, there will be a few thousand foreign soldiers still training the Afghan security forces and hunting international militants in the most lawless parts of the country. He is currently demanding further concessions from the US, and some diplomats have concluded he will not sign the deal.

If he doesn't, the future of relations between Afghanistan and the international community that pays for its government and army will hang on the election. Without the military deal, funding will probably be limited; the US has already halved its aid budget this year. And the collapse of the Soviet-backed government in 1992 was precipitated not by the departure of Soviet troops three years earlier but the abrupt halt funds that paid the army's salaries.

2. The candidates

There are 11 candidates, ranging from the man who first invited Osama bin Laden to Afghanistan to a chatshow host and retired pilot. Here are a few details about the frontrunners (in alphabetical order).

Abdullah Abdullah

Born 1960. An ophthalmologist who swapped surgery for the battlefield as a prominent member of the anti-Soviet resistance, Dr Abdullah, as he is commonly known, is the only serious candidate whose main power base lies outside Afghanistan's Pashtun ethnic group. Born to a Pashtun father and Tajik mother in Kabul, much of his standing among Afghans comes from his close ties to the assassinated Panjshiri mujahideen commander Ahmad Shah Massoud. Originally Hamid Karzai's foreign minister, he resigned in 2005 and four years later surprised many observers by emerging from a messy opposition field to pose the only serious challenge to Karzai, wining enough votes to force a disputed second round in the 2009 poll. He dropped that challenge but stayed out of government as other contenders took senior posts, focusing instead on building up a grassroots support network. Afghanistan's complicated ethnic politics mean he is expected to focus on sweeping to a first-round win, as he would be struggle in a second-round showdown that would potentially unite the Pashtun vote behind another contender.

Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai

Born 1949. A technocrat intellectual turned nationalist, Ghani is a former finance minister and World Bank official with the most detailed political platform of any candidate, but only a slender political base. He also campaigned in 2009 and won just 3% of the vote. This time he has made a more direct bid for power, allying himself with a controversial but popular former militia commander, Abdul Rashid Dostum, whose solid block of votes could be enough to push Ghani into the second round as the main Pashtun candidate. The decision to line up beside a man accused of letting hundreds of Taliban prisoners swelter to death in shipping containers, and other war crimes, lost him the support of some young pro-reform voters who are his most obvious constituency. He countered the criticism by wringing a reluctant but public apology of sorts from Dostum - the first such acknowledgement of civil-war-era wrongs.

Qayoum Karzai

Born 1957. The president's older brother, who has none of his mujahideen credentials or political charisma. He was in the US running restaurants when Hamid was in Pakistan as part of the anti-Soviet movement, only returning after the Taliban's fall. Qayoum established a network of profitable businesses in the family's hometown, but kept a far lower profile than other Karzai brothers – the Kandahar strongman Ahmad Wali and businessman Mahmoud. But Ahmad Wali was assassinated in 2011, and Mahmoud has been dogged by his connection to failed the Kabul Bank scandal, leaving Qayoum the most obvious family contender to stay on in the presidential palace. He has some political experience after winning a seat in parliament in 2005 elections, but resigned when attendance records were published showing he barely turned up. He has had public spats with his brother, whose support is by no means guaranteed, but his family name and connections could provide formidable help even without the incumbent. He is believed to have given up US citizenship to run in the election.

Nader Naim

Born 1965. A grandson of the former King Zahir Shah, whose rule is still remembered by some Afghans as a golden age, Naim is a relatively young candidate who complains about being ignored by the media. Born in Afghanistan, but raised in the UK after his grandfather was toppled by his uncle in a bloodless coup, he returned only after the fall of the Taliban. Working as a secretary to his grandfather, now an ordinary citizen, he built up a wide network of contacts that will bolster his campaign, although it is unclear if he will be able to bankroll a serious bid in what is likely to be an expensive election.

Abdul Rasul Sayyaf

Born 1946. A former mujahideen leader and hardline Islamist, he is the man who first invited Osama bin Laden to Afghanistan after he was ejected from Sudan. He also gave his name to the Philippine insurgent group Abu Sayyaf, and the 9/11 commission reports mention him as "mentor" to the attack's mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. In Afghanistan, his political contributions have included opposing women's rights provisions and helping pass a bill giving amnesty to those who committed war crimes during the country's brutal civil war. He is generally thought to be too hardline to win even in modern Afghanistan, but like Ghani has teamed up with a popular former militia leader – Ismail Khan, commander and then governor of western Herat – who can command a block vote.

Zalmay Rassoul

Born 1942. An elegant doctor, former foreign minister and distant relative of the deposed king, Rassoul is the only candidate to have a woman on his slate and even after years in government has stayed untainted by the allegations of corruption that have followed so many other officials. He has known Karzai for decades and they worked together in Rome before the fall of the Taliban. He is the oldest and – on his own – one of the politically weakest candidates, but many analysts believe he has the current president's backing, because of their close relationship. If Rassoul won with Karzai's support, the current president could potentially continue to exercise considerable power from behind the scenes. Still, he faces substantial obstacles. He is not married, which is extremely unusual in conservative Afghanistan, and generally viewed with suspicion. Although ethnically Pashtun, he has been a Persian speaker all his life, and is reportedly only now learning the language of the people who in Afghanistan's ethnically charged political scene should be his main supporters.

Gul Agha Sherzai

Born 1955. A colourful, divisive man, nicknamed "the bulldozer", Sherzai was born the son of a poor restaurant owner and rose to wealth and power as a mujahideen commander. The governor of southern Kandahar province before the Taliban's ascent, a time when accusations of abuse were rife, he recaptured the city with help from US forces in 2001 and was reinstated in power. For years he enjoyed a close relationship with the United States, but it has soured recently over allegations of corruption. After he moved to eastern Nangarhar province in 2005, he is reported to have made millions because the job brought control of the lucrative border crossing into Pakistan. He denies any corruption, and is proud of a nickname he claims is tribute to his ability to get building projects done; he has widespread popular support won in part by disbursing some of his vast fortune to ordinary people ranging from school teachers to soldiers short of funds for marriage.

3. The vote

The election is in two rounds, similar to the French system. If no candidate gets more than 50% of the vote in the first round – which with 11 candidates is unlikely, unless someone reverts to massive fraud – a second round must be held pitting the top two candidates against each other.

That means that although the poll is set for 5 April, the process could drag on for months. Getting the ballot papers back from far-flung stations and handling complaints is expected to take weeks, with a final result not due until mid-May.

A second round would take at least six weeks more, probably longer. So even though the president, Hamid Karzai, is officially due to step down in May, many observers think the country will not get a new leader until July or August at the earliest.

The election is run by the Independent Election Commission (IEC). Any grievances are handled by the Electoral Complaints Commission, which has already thrown out more than half the would-be presidential candidates for not meeting requirements.

Around 12 million of the country's estimated 30 million people are eligible to vote, if they have a voter registration card. But in a worrying sign of challenges ahead, there are potentially around 20 million of these makeshift identity cards in circulation in Afghanistan. Most were handed out during previous elections, but more than 3 million more were created in a registration drive last year that officially targeted those who had newly turned 18, lost old cards or returned from abroad.

The system is weak on controls, and the cards, which can be used at any polling station around the country, are easily transferred. They were for sale long before the election campaign kicked off.

Women's cards are particularly useful for anyone looking to evade "one person, one vote" rules, as they do not have to carry photos out of deference to cultural sensitivities in conservative communities about strangers seeing women's faces.

There are 6,845 voting centres, and the election organisers say they expect 95% – 6,431 – to open on polling day. Still, last time round polling booths in many areas were open but empty, so there is no guarantee of participation.

Casting a ballot involves hours of travelling and serious risks for many Afghans. Massive fraud in previous elections has left many disillusioned about the process, or at least unwilling to risk their lives.

The Taliban have slammed the election and anyone who participates. Last year they killed an election official and boasted about it on Twitter. The group's leader had already denounced the vote as a "waste of time" and said "pious people" would not participate.

Security will mostly be provided by Afghan security forces, although the shrinking Nato mission has offered help with logistics, including air transport of ballots and other supplies. Afghanistan's rugged mountains, harsh deserts and limited infrastructure mean organisers of past elections have relied heavily on both high-tech air transport and traditional solutions such as donkeys to get ballot papers and boxes to more remote areas.

The election is held at a time when Afghanistan is only just emerging from a bitter winter, but this year has been unusually dry so areas that have been cut off by snow in April of past years are much more likely to be accessible.

4. The tactics

The election is a wide-open field. There is no incumbent and no clear frontrunner at present, making the stakes even higher for those who are competing.

Everyone agrees that given the challenges of running an election in Afghanistan, the prize at stake and the budgets some candidates have built up, there will be fraud. The only question is how much.

Diplomats working on the vote say the result only has to be "good enough" – fraud that is not truly outrageous, and a candidate who most Afghans can broadly accept.

They point to elections such as the 1994 poll in South Africa that brought Nelson Mandela to power, when there was corruption but everyone agreed the result matched the will of most people – though Afghanistan is a long way off having its own Mandela figure.

Candidates are likely to be weighing up what combination of condoning and combatting irregularities offers the best chance of victory, and few people believe anyone will stick to the official campaign budget cap of 10m Afghanis (£107,000).

There will be few independent observers outside big cities, but all campaigns say they will deploy monitors to every voting station they can to look for irregularities. The complaints process will almost certainly be as hard-fought as the campaign, and plenty of time has been left for candidates to file and settle grievances.

Abdullah Abdullah, who had a Tajik mother and a support base among non-Pashtun northerners, is likely to come top in the first round but only claim victory if he can stagger over 50% then. If it goes to a second round, supporters of the main Pashtun candidates are expected to mostly unite – even if reluctantly – around the other candidate and put him ahead.

Karzai has played his cards close to his chest, perhaps to enhance his status as kingmaker or give him a greater chance of a major role in the government of the eventual winner. He has said several times that his only role in the election will be casting his personal vote, but behind the scenes he is expected to deploy considerable political and financial influence for whoever he backs.

One of the biggest fears for the vote's overall credibility, and a major concern for some Pashtun candidates, is the risk of an inadvertent ethnic disenfranchisement.

Pashtuns are Afghanistan's largest ethnic group, though not an absolute majority of the population, and have provided all but one of the country's leaders over the last hundred years.

But they are also the group from which the Taliban originally hailed, and most live in the south and east, where the insurgency is strong and election violence expected to be high.

There are fears that if Pashtun voters are kept away or scared away from polls in disproportionate numbers, and those who do go to vote elsewhere select a non-Pashtun, it could exacerbate anti-government sentiment and feed support for the insurgency in these areas.

There was a smaller-scale example of this in 2010 parliamentary elections in eastern Ghazni province, where the population is a mix of Hazaras and Pashtuns. But violence is concentrated largely in Pashtun areas, so all 11 members of parliament selected were Hazara. The result roiled the province and parliament for months.

But others argue those worries are overstated, pointing out that all the three-person slates for the election are reassuringly multi-ethnic, and there are serious problems with violence in other parts of the country as well that will affect voter turnout. The insurgency now has supporters of all ethnicities nationwide.

5. The in-tray

There will be two main files – poverty and the insurgency – though it is questionable how much power the new leader will have to do much about either problem. Other major issues will be the flourishing drugs trade and thorny relations with both neighbours and world and regional powers.

Corruption is eating away at Afghan society, already battered by decades of war. If the new president fails to rein in graft at least a bit, he will struggle to hold on to whatever popular support he garnered to get into office.

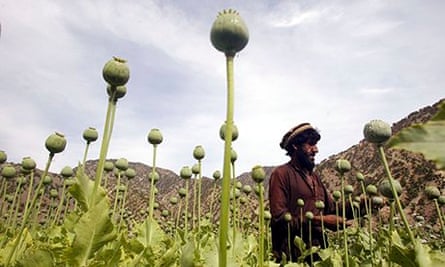

The new president will also have to decide what, if anything, to do about opium production, currently at record levels. It fuels both graft and the Taliban, and a senior UN official recently warned that it risked turning Afghanistan into a fragmented criminal state.

But it is also the main income for many poor farmers, who currently reap little of the multibillion-dollar profits and may have no other options to support their families. Attempts at eradication have been bloody and unsuccessful overall, so any change is likely to be slow and difficult.

The insurgency is still raging, and the president will have to inspire the security forces, choose generals to lead the fight, and plot tactics to beat a tenacious and experienced enemy. Many Afghans are fearful the fighting will explode again into a full-blown civil war, ripping apart a decade of development in cities that have stayed relatively calm, such as Kabul and northern Mazar-e-Sharif.

The economy is the elephant in the room. The government and international community are so focused on the violence that it rarely seems to be a top priority.

Yet the economy's weakness fuels the insurgency as some of the young people who can't find jobs turn to the Taliban, fighting for salaries similar to those offered by the national police and army. Tax revenue is tiny, the government can't pay for itself or its security forces, and there is little hope of that changing unless and until major mining projects still in very early stages of development start up; the president will have to coax wary investors from planning to actual production.

If Karzai does not sign the bilateral security agreement with the US, the new president will have to decide if he is willing to keep American forces on Afghan soil in return for cash and military support.

He will also have to negotiate difficult relations with neighbours Iran and Pakistan, which both play host to large populations of Afghan refugees, have a keen interest in the country's affairs, and have for decades poured resources into influencing Kabul, often to the frustration of many Afghans.

Ties with other regional powers may be less fraught, but for a landlocked country are still vitally important, and while Afghanistan is still dependent on foreign aid managing its diplomatic ties to the west and other nations such as Japan that provide substantial support will also be a priority.

6. The data

Since 2001, Afghanistan's GDP has risen annually. In 2012, the country's GDP was $20.4bn (£12.4bn), a 14% increase from 2011.

Inflation

Fluctuating prices continue to affect the country. After a sharp increase in 2011, the country's inflation rate dipped slightly in 2012 to 7.2%.

Unemployment

Data on unemployment rates in Afghanistan is weak and controversial, according to an EU National Risk and Vulnerability assessment (PDF), because they fail to capture the situation for most Afghans who are chronically underemployed, working several hours a week, but cannot afford to be unemployed.

Civilian casualties

In the first six months of 2013, 1,319 Afghans died and 2,533 were injured, mostly as a result of improvised explosive devices used by anti-government groups, but also as a consequence of increased fighting in 2013 between those groups and Afghan forces.

Education

The number of children enrolled in Afghan schools has more than quadrupled since 2001, with 97.4% enrolled as of 2011. Gross enrolment figures include students of all ages, including those who are repeating or are starting school early, and therefore sometimes exceed 100%.

Drugs

Despite eradication efforts, the total area of Afghan land under opium poppy cultivation rose in 2012 to an estimated 154,000 hectares, an 18% increase since 2011 and a reflection of relatively stable farm-gate prices and world-wide demand. The production of opium, however, decreased by 36% due to a combination of disease and adverse weather in 2011.