It is a ship that has launched a thousand tales.

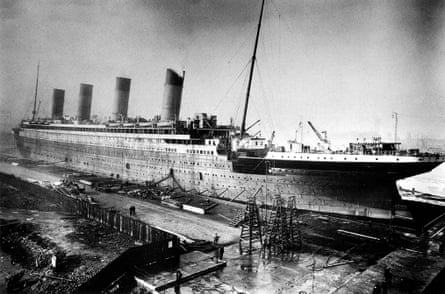

More than 100 years after its sinking in the north Atlantic, the Titanic endures in the public consciousness. The glamour, the heroism, the treachery, the sheer tragedy of the disaster has spawned dozens of films – including one made just 29 days after the liner sank and a German Nazi propaganda movie with a German first officer cast as the hero. There’s also a musical, a song that became one of the bestselling singles of all time, and a plot device that threatened to thwart the Crawley ownership of Downton Abbey.

At any given time, somewhere in the world there is likely to be a Titanic exhibition, and this week it was Melbourne’s turn.

Staged by RMS Titanic, Inc.– the only organisation authorised to salvage from the wreck and conserve its artefacts – the exhibition at Melbourne Museum is of blockbuster proportions.

Along with about 200 artefacts salvaged from the doomed steamship – including unopened bottles of champagne, stoppered perfume bottles, luxury interior fixtures and part of the liner’s hull – there are recreations of first and third-class cabins, the grand staircase with cherubic ornamentation that became an iconic set in the 1997 James Cameron film, and the offending iceberg itself, which will tolerate being touched by visitors but will not be giving interviews. NBC’s Saturday Night Live still has that exclusive to its name.

In Australia this week to oversee the exhibition’s installation were RMS Titanic, Inc’s president Jessica Sanders and the company’s resident historian James Penca, who became enthralled by the subject after visiting a similar exhibition as a school student in Cleveland, Ohio, 25 years ago.

“The Titanic story is, in my opinion, the greatest story ever told,” Penca tells the Guardian.

“There is no story in history, fiction or nonfiction, that is as grand, as romantic, as heroic and, yes, as tragic as the Titanic.

“When people see the word Titanic, they’re filled with so many emotions; it’s an incredible story that we will be forever drawn to.”

The Titanic has long been a favoured setting for doomed romance, but while the Jacks and Roses of Cameron’s Titanic are pure fiction, Penca says there were plenty of real tales of love and loss to be found in the aftermath of the liner’s ill-fated maiden voyage.

A number of survivors’ testimonies recall seeing a young married couple meeting at the gates separating second and third class on consecutive days; the young man had bought himself a third-class ticket but wanted his wife to be more comfortable in second class. She survived, he did not. Another young gentleman impulsively bought a ticket to follow his secret love back to New York. The paramour only declared his presence and the couple’s intention to marry to the woman’s parents as the ship was sinking. He commandeered one of the lifeboats and saved the entire family.

“There are so many testimonies where women – and of course many more women than men survived – describe the loss of their soulmate, their best friend, which is extraordinary given that in 1912 so many marriages, certainly among the upper classes, were still transactional in nature,” Penca says.

Such testimonials are overwhelmingly sourced from the Titanic’s wealthiest passengers, because they were the ones who were asked to give evidence at the subsequent Senate inquiry, Penca says. They were the ones who the media clamoured over to tell their stories.

They were also members of the social strata that had the highest survival rate, with almost two-thirds of the Titanic’s first-class passengers living to tell their tales. Only four women travelling in first class perished in the disaster, and at least one of those – Edith Evans – willingly gave up her seat in the lifeboat for another woman she had befriended during the voyage. Of the 709 third-class passengers, only 174 survived.

The socioeconomic demographics on the Titanic are a fascinating study in class division, RMS Titanic, Inc’s president says.

“You’ve got these first-class passengers who were definitely the who’s who of their time and on the same vessel are hundreds of people coming from poverty, emigrating to America and hoping for a better life,” she says.

“But in reality, many of those third-class passengers would have experienced a level of accommodation they had never seen before in their lives.”

The marked difference between the classes on board is not only captured through the vastly different spaces and furnishings of the first- and third-class cabins recreated in Melbourne Museum, Sanders says. The menus for the separate classes and the china the meals were served on are also on display.

Also included in the exhibition are the stories of the five Australians on board, four of whom were crew members. The only Australian to survive was 28-year-old Evelyn Marsden, from Dalkey in South Australia. The inquiry into the Titanic’s sinking heard that Marsden had been engaged on the vessel’s maiden voyage at a salary of three pounds and 10 shillings a month (about $461 in today’s currency), to work as a stewardess with a side-line in nursing duties. But it was her skill as a rower – which she had learned as a child on the Murray River – that saw her captain one of the lifeboats and, avoiding collisions with icebergs in the freezing North Atlantic sea, safely pilot the craft to the rescue ship Carpathia.

Another tale of remarkable survival came from the occupants of one of the last lifeboats to be launched off the sinking ship. When the Titanic broke in two, this lifeboat narrowly missed being crushed by the collapsing first funnel. The survivors spent the night standing on the bottom of the upturned craft, rocking back and forth together to keep it afloat. Only a pocket of air under the boat prevented it from sinking.

As a Titanic historian, Penca spends much of his time in media interviews busting the myths that have swirled around the tragedy for more than 100 years. The White Star Line never claimed the steamship was unsinkable – “practically unsinkable” was the phrase the company used.

The heavy casualties suffered in third class were not the result of passengers being trapped behind high iron gates that were locked during the evacuation process, as was portrayed in the 1997 film.

“There’s actually no evidence [on the wreck] to say that that ever happened,” Penca says.

“Testimonies from third-class passengers described hopping over the gates separating third- from second-class, they were only about waist high.”

Stories about men cross-dressing to steal a seat on a lifeboat also appear to be somewhat exaggerated. The inquiry heard from one survivor who admitted to throwing a woman’s shawl about his head and clasping the arm of a fellow female passenger to gain a seat on a lifeboat, of which there were only 20.

While it is true that number was only about a third of what a ship the size of the Titanic should have had to accommodate all 1,496 passengers and crew, Penca believes an adequately equipped vessel would have probably made little difference to the final death toll.

“Things didn’t get crazy until the very last 30 or so minutes,” he says. “When the iceberg strike happened, everyone thought it was going be okay … 18 of the 20 lifeboats were successfully launched, and there just wouldn’t have been enough time to launch any more before the funnel fell and the ship broke in half.”

The villain of the tragedy also appears to have been unfairly maligned, Penca believes. In the 1997 film Englishman J Bruce Ismay, the chairman and managing director of the White Star Line, who was on board, is shown persistently urging Captain Edward J Smith to go full throttle, to ensure the Titanic met its arrival schedule in New York City. Smith went down with the ship, Ismay survived.

“Not only is there very little evidence to suggest that Ismay ever wanted the ship to go faster, but he actually spent the entire sinking helping load lifeboats, ” Penca says.

“He saved a whole bunch of people, and then when it was down to pretty much the last lifeboat, there were no women and children left in the starboard area. There was no one else who would get in the boat. He took a spot and thank God he did because from a research point of view, his evidence was incredibly valuable.”

Titanic: The Artefact Exhibition is showing at the Melbourne Museum until 14 April 2024.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion