What a wonderful and wonderfully bad painter Henri Rousseau was. There is even something touching and gauche about the big, wonky signature that always decorates a corner of his paintings: it is as if the painter were amazed to find himself there. The conundrum of Rousseau also depends on the fact that when things went wrong in his paintings, their very wrongness - anatomically, or in terms of perspective - more often than not feels right, or so out of whack and unlikely that what is lost in terms of believability is gained in character and presence.

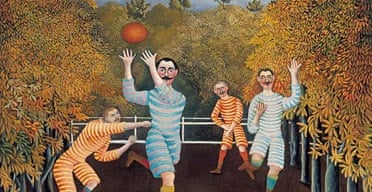

Rousseau could get away with all kinds of awkwardnesses and academic defects, and with much silliness. His clouds are mad, his botany and zoology are barmy, his sunsets are alarming. The spots on a leopard, a bird's plumage, a tiger's stripes he could paint very well, but when it came to footballers' striped jerseys, or human hands or feet or faces, something hapless and laughable occurs.

For which, of course, we forgive him. It is 80 years since a Rousseau exhibition came to London. Tate Modern's show, which will travel to Paris and Washington, opens on Thursday. And it opens not with Rousseau himself, but with King Kong, or one of his cousins, a huge academic 1887 sculpture by Emmanuel Frémiet of a fearsome gorilla, carrying off a naked maiden. This bronze monstrosity stands in a wallpapered Rousseau jungle, as if to announce that here there be terrors, but don't for one minute take any of them seriously.

This startling preamble to the exhibition, which covers the whole of Rousseau's career as a painter, from about 1880 until his death in 1910, is also meant, I think, to forewarn us of French attitudes to the exotic in the late 19th century, an idea of dark continents, wild beasts and brute savagery essentially no different to the ones found in the stories of Jules Verne or Arthur Conan Doyle. At least in Rousseau's art there's no hint of colonialist superiority.

"The lion, being hungry, hurls itself on the antelope, devours it; the panther anxiously awaits the moment that she too will have her turn," Rousseau wrote of his 1905 painting, The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope. "Carnivorous birds have each torn off a piece of flesh from the underside of the poor animal as it lets fall a tear! The sun sets."

The red sun sinks beyond the trees, turning the clouds pink. An owl stares straight out of the painting, a gobbet of flesh in its beak. The cool light filters between the tree trunks at this peculiarly still hunting hour. This is typical Rousseau: the abrupt violence of the lion's attack, and all those eyes, bright against the forest gloom, all those leaves silhouetted against the dying light. But the jungle somehow looks too temperate than it ought. And what, one would like to ask the artist, is that other creature, who goes unmentioned in Rousseau's little accompanying text, lurking half-hidden amidst the foliage?

Gorilla? Sloth? Yeti? It is the biggest animal in the picture, a great hairy thing that stands like a man, but with the eye of a bird, and most certainly a creature Rousseau would have been unlikely to find in the filthy, dispiriting cages of the zoo in Paris's Jardin des Plantes. Nor would it have been among the 23,000 bird and 6,000 mammal specimens in the taxidermological displays of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, from which he transposed the central event in this painting, the stuffed arrangement of a Senegal Lion Devouring an Antelope, to a fanciful setting all his own.

The stuffed lion and antelope are also here in London, in a room devoted to Rousseau's source materials and other ephemera, including early Pathé comic films. Rousseau, who put about the story that he had seen the jungle first-hand while in the army in Mexico, in fact never left France, and only joined the army after cheating his employer, a solicitor, out of a trifling sum of money and some stamps, for which he spent a month in jail in 1864. His knowledge of jungles and animals was entirely derived from the zoo and from the taxidermic museum that opened in Paris in 1889.

Rousseau took up painting in the early 1880s while working at a customs post, collecting tariffs on goods entering Paris. His aim, it appears, was to become an academic painter. He copied in the Louvre, he sought advice from leading pompier painters of the day, and remarked that the academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme had advised him: "If I have kept my naivety, it is because Monsieur Gérôme always told me I should keep it."

Gérôme may have been astute, but he may equally have been joking at Rousseau's expense - though we should be just as suspicious of Rousseau's supposed innocence and naivety, as a man if not as a painter. Towards the end of his life, in 1907, Rousseau was implicated in a fraud trial, and his defending lawyer later wrote that "Rousseau always remained an enigma for me. Was he a man mystified by everything, or was there something of a mystifier in him?" Ambrose Vollard also wondered whether, underneath everything, Rousseau "was a sly old dog". At the trial, Rousseau even produced his own paintings as evidence of his naivety.

Rousseau's paintings glow against the grey walls in Tate Modern's exhibition. Almost everything about them is a fanciful concoction, whether he was painting jungles of plants and trees that barely belong in the same hemispheres, let alone latitudes or climate, or scenes of suburban Paris which, although sometimes begun as faithful topography, took on an aspect entirely derived from the artist's imagination. He is regarded as a kind of collagist - equally happy cribbing a tiger's pose from Delacroix or a lion from an illustration in Le Petit Journal, for which he briefly worked as a sales representative. Academic sculptures, postcards, a book of wildlife pictures and his lone expeditions to the Jardin des Plantes provided his material.

The result was often extremely odd: what is a white horse doing in the jungle? How might a fully head-dressed native American find himself in combat with a gorilla? And what are the monkeys in the jungle doing with a milk bottle and a back-scratcher? Little wonder André Breton regarded Rousseau as a proto-surrealist.

There is also something strangely metaphysical, if not surreal, about the atmosphere of Rousseau's silent and still suburban streets, his quays on the Seine and forgotten corners of Paris. People walk well-tended gravel paths that seem to peel away from the earth, disobeying the laws of perspective, or make their way along quiet streets towards a vanishing point that will arrive before they can reach the house on the corner. Telegraph wires become as fanciful as jungle creepers. But somehow none of this matters. People wait; they pass by; anglers fish; nothing happens, and there is a sense of waiting, of imminence, of emptiness. A group of identical artillerymen pose around their cannon. The same faces, the same moustaches. How much of all this was intentional?

As Christopher Green writes of the jungle paintings, in one of a number of excellent essays in the Tate catalogue: "Those red suns behind the trees suggest more strongly the slowly fading winter sunsets of the Bois de Boulogne than the briefly brilliant sunsets of the tropics. These are tropical forests for northern imaginations." Rousseau's blood-red setting suns and white moons rising over the forest canopy remind me of the ossified forest paintings of Max Ernst, just as it is difficult to look at his street scenes without thinking of De Chirico and Salvo. In fact, you can see Rousseau all over the place in the art of the 20th century. He was never only Picasso's pet.

But what can we do with Rousseau's snake charmers, or the woman whose divan has been transported into a frolicsome jungle Eden? Can we still believe in them? While he could never be accused of being a great painter, Henri Rousseau was instead a maker of marvellous and memorable images. One of the reasons people have been drawn to his art is because we are somehow made aware that behind his exotic paintings lurked a personality who - we like to think - exceeded his untutored skills and overcame his patent deficiencies by dint of a rich poetic imagination. This version of the artist is not exactly truthful (such assumptions rarely are).

Rousseau's appeal is to the child in all of us. He gives us back a sense of wonder. But like all the best children's stories, his works are full of darkness, violence and mystery. This is why he's worth returning to, and why he is so popular. Rousseau himself remains the biggest mystery of all.

· Henri Rousseau: Jungles in Paris is at Tate Modern, London SE1, from Thursday until February 5. Details: 020 7887 8888.