If you’ve traveled abroad, you’ve probably seen the warnings. Outside the United States, cigarette packages are affixed with gruesome pictures of lips, teeth, and lungs damaged by smoking-related diseases. Such pictorial warnings have become the gold standard across the world for conveying smoking’s risks. Well over 100 countries require them. They are disturbing to look at—in Thailand, cigarettes have featured a gaping tracheotomy hole; in Brazil, a man with legs amputated below the knees; in Singapore, a foot mangled with gangrene. The U.S. is an outlier, with our inconspicuous, text-only warnings on the narrow side of a cigarette pack.

This summer, a federal court is set to hear one of the biggest tobacco cases in U.S. history, which will decide if our tobacco warnings will finally catch up to those of our global peers. The case was brought in 2020 by R.J. Reynolds and other cigarette companies against the Food and Drug Administration. It’s the latest battle in a long legal saga: Congress mandated pictorial warnings in 2009, but the tobacco industry has held them off with claims that the warnings violate the First Amendment.

The case is being heard by the conservative 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, where 12 of 17 active judges were appointed by Republicans (six by Donald Trump). The Biden administration is defending a set of pictorial warnings developed by the FDA under both Obama and Trump. If the 5th Circuit rules against the FDA, it would be years before we might see pictorial warnings on cigarettes. At stake in this case is the First Amendment’s role in mandated product warnings, the power of administrative agencies, and the future of smoking-related death and disease.

The story of this case begins in 2009, when Congress enacted the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, the most comprehensive set of tobacco restrictions ever passed in the U.S. That law, passed with bipartisan support, required that cigarette packages and cigarette advertising include 1 of 9 text labels, such as “WARNING: Tobacco smoke can harm your children” or “WARNING: Cigarettes cause strokes and heart disease.” Congress empowered the FDA to modify these warnings or add others. These rotating warnings would replace the blander variety of text warnings that have been on cigarettes since 1965. (The text-only cigarette warnings we are stuck with today have been unchanged since 1985.)

That law also required the FDA to develop color images to accompany each warning, to add visual punch to the text. It stated that the graphics must occupy at least 50 percent of the front and back of each cigarette pack and 20 percent of every cigarette advertisement. That’s a dramatic expansion of marketing real estate for warnings.

No doubt these were aggressive measures, but Congress found that other steps to curb smoking were inadequate. Academic studies show that text warnings are less effective at dissuading new smokers and that graphic warnings are particularly effective for teenagers and low-literacy smokers. One peer-reviewed study concluded that graphic warnings would reduce smoking prevalence in the U.S. by 5 percent in the first few years and over a 50-year period would likely avert 652,800 deaths and 73,600 preterm births.

In 2011 the FDA finalized nine images to accompany the new text warnings for cigarettes. The images were accurate—and upsetting. One showed yellowed teeth and a cancerous lip. Another showed smoke coming out of a tracheotomy hole in a man’s neck. Each graphic had a toll-free number on it: 1-800-QUIT-NOW.

But cigarette manufacturers refused to use them. R.J. Reynolds and other tobacco companies sued, alleging that the FDA’s graphics violated the First Amendment. They said the FDA was compelling them to convey the ideological message of the government, curtailing their free speech rights.

There were no prior cases about how the First Amendment applies to mandated pictorial warnings. Courts have ruled for decades that the government cannot compel anyone to speak political messages. But courts have also upheld requirements that companies disclose factual information about their products. Under this “commercial speech” doctrine, disclosure mandates are permissible so long as they are “reasonably related” to a governmental interest, such as public health, energy conservation, or consumer protection. The doctrine covers things like fuel-economy stickers on cars, country-of-origin labels on meat, and disclosure of artificial colors or flavors in food.

The tobacco companies claimed that the FDA’s images were not disclosing facts, like the gas mileage on a car, but were instead designed to trigger emotions to quit smoking. That’s a First Amendment violation, they asserted, because the FDA was making private companies convey controversial government messaging.

In 2012 the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed and sent the FDA back to the drawing board. It said the agency had to develop a less “provocative” set of images, ones that conveyed accurate information but did not “browbeat consumers into quitting.”

That ruling put the FDA in a bind. The Tobacco Control Act had commanded the agency to develop graphics “depicting the negative health consequences of smoking,” but now the courts were saying the graphics couldn’t be too provocative and couldn’t “evoke emotion.” But how can accurate images of smoking’s harms—cancer, lung disease, death—not evoke emotion?

Around the same time, the tobacco industry brought a separate suit to get large portions of the Tobacco Control Act struck down on First Amendment grounds—a frontal attack on the legislation—but that suit was rejected by the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals. That court found that current warnings are “easily overlooked” and that “larger warnings incorporating graphics promote a greater understanding of tobacco-related health risks and materially affect consumers’ decisions.”

These court decisions from a decade ago put us in the strange situation we’re in now. The Tobacco Control Act remains on the books and was upheld under the First Amendment, including its requirement to devote 50 percent of cigarette packaging to warnings. But the FDA’s implementation of the law has been micromanaged by the courts, down to the content of specific images.

The FDA deserves some of the blame for the holdup since 2012 because, after the D.C. Circuit’s decision, it was sluggish in designing new graphic warnings, and the project lasted well into the Trump administration. It took another lawsuit (this time brought by public health groups) to compel the agency to act. In 2018 a district court judge in Massachusetts ruled that the FDA had “unlawfully withheld” and “unreasonably delayed” action to revise the graphic warnings.

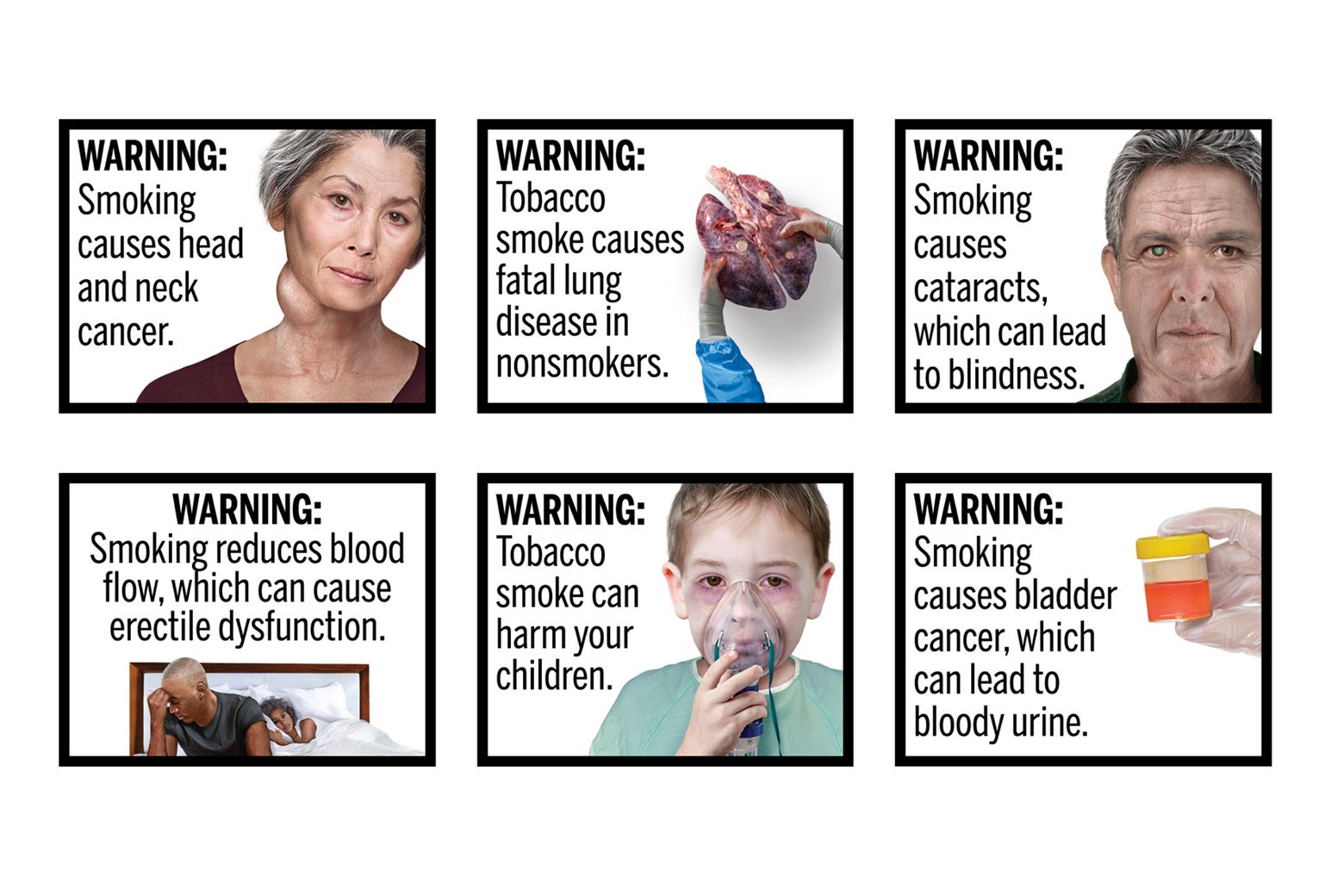

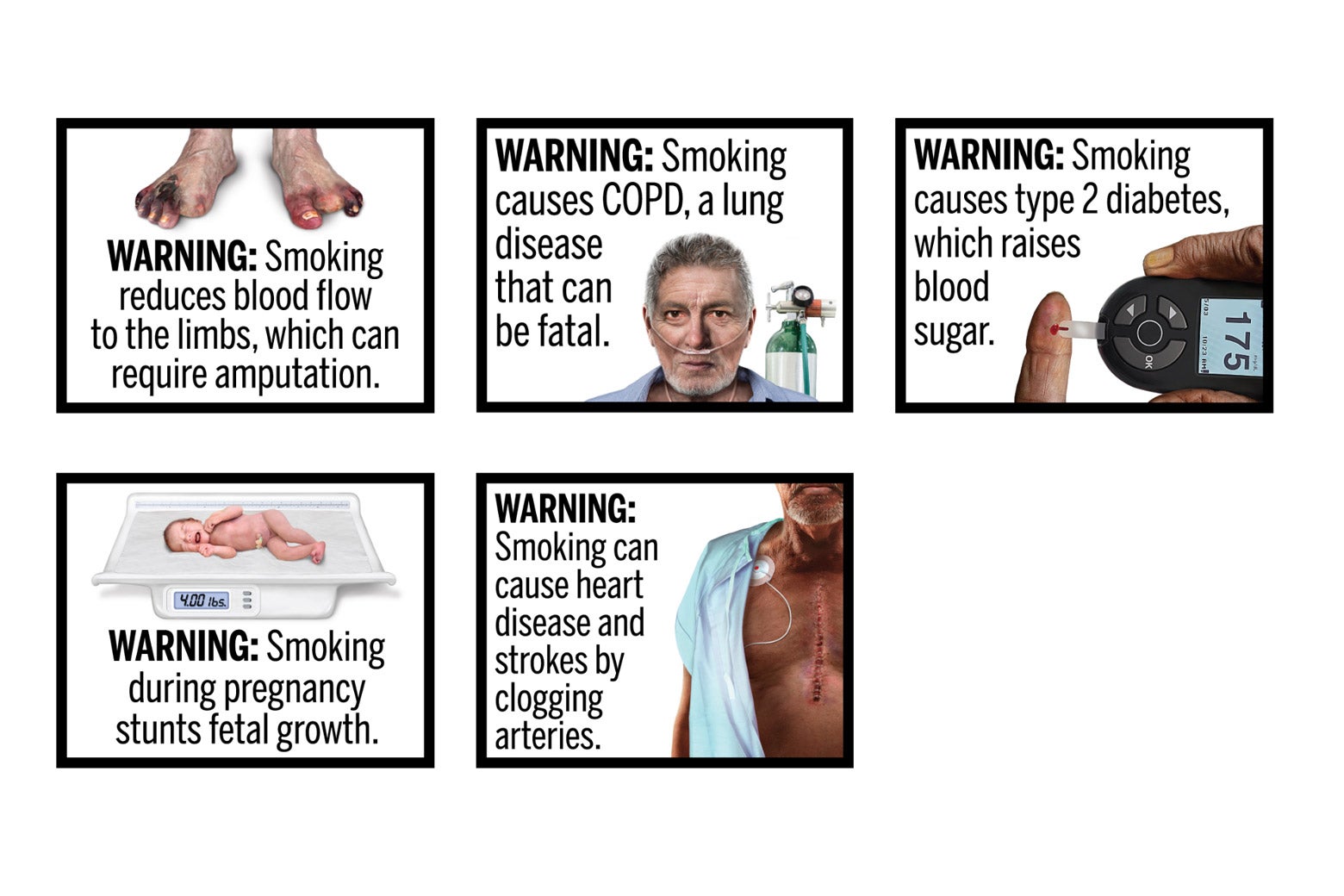

In 2020 the FDA finally decided on a new set of 11 images to fulfill Congress’ mandate. Compared with the 2011 images, these were toned down—no more tracheotomy holes—and the FDA dropped the 1-800-QUIT-NOW number that the courts had specifically criticized.

The agency made other changes to increase the odds that the images would survive First Amendment review. It chose to focus on less well-known risks of smoking, like diabetes and cataracts, to counter the tobacco companies’ claim that the warnings serve no real purpose because the public is already aware of smoking’s health hazards. The new images are medical illustrations rather than photographs, and each was tested through consumer studies. Each image straightforwardly depicts the related text warning. For instance, a warning that smoking causes Type 2 diabetes is accompanied by a graphic of a finger being pricked by a glucose monitor.

None of this satisfied R.J. Reynolds and the other tobacco companies. In 2020 they sued again, strategically judge shopping to ensure a favorable outcome. Although the FDA issued the new warnings in Washington, the tobacco giants sued the FDA in Tyler, Texas, where there are only two federal judges, both Trump appointees.

Their strategy paid off. Last year, Judge J. Campbell Barker tossed out the FDA’s revised graphics. He ruled that they were not “purely factual” and “uncontroversial” but instead impermissibly “provocative” and “value-laden.” Focusing on the FDA’s image of a woman with a neck tumor, he said that some consumers “might interpret the depicted person’s gaze … as expressing regret at her choice to smoke,” thus conveying an ideological message that “smoking is a mistake.” He added that the images failed to show the most “common” or “typical” results of smoking. It is Barker’s ruling that the Biden administration has now appealed to the 5th Circuit.

The 5th Circuit should reverse Barker’s ruling, which overly handcuffed the FDA. The agency cannot control what emotions arise in viewers of these images, and there is no way a single image can convey every possible outcome from smoking. Not every smoker will develop head or neck cancer, of course, but the FDA’s images show factual outcomes that many smokers do suffer. The First Amendment does not demand banality. These are, after all, warnings, and they should be allowed to depict severe outcomes. Most people overlook the existing text warnings and are unaware of the full range of diseases that smoking can cause—until it is too late.

This whole saga shows how hard the tobacco giants will fight to duck the Tobacco Control Act. They know the stakes. Putting graphic warnings on both cigarette packages and advertisements would be the biggest change to the industry since it settled more than $100 billion in state Medicaid claims in the 1990s. Smoking rates have declined dramatically since the Tobacco Control Act was passed, as people have quit or switched to vaping. But smoking is still the leading cause of preventable death and takes more than 480,000 lives annually in the United States, damaging the health of countless more people along the way.

If the 5th Circuit upholds Barker’s decision and vacates all 11 images, it’s not clear what would ever satisfy the courts. A childish cartoon of a mouth with a warning about mouth cancer? A bar chart of cancer risks? If the only images that are constitutionally permissible are those that are bland, those images would not convey vital information. Bland visuals would actually be misleading.

Given the conservative tilt of the 5th Circuit, it’s likely that the court will find some flaw in these revised images and send the FDA back for another rule-making process. That would likely take two or three years (followed by another round of litigation).

If the court upholds the FDA’s revised set of images and warnings, the tobacco giants will undoubtedly appeal to the Supreme Court, where they are likely to receive a favorable reception from the court’s six conservatives. In the meantime, millions of Americans, who have long ignored the current text-only warnings, will continue to suffer from their addiction to smoking.