The post below was written six months ago. At the time it had to remain unpublished, an art related secret yet to be told. Things have moved on, I can now tell the story.

27 February 2019

I am writing this knowing that for the time being at least, I’m not going to be publishing this post. The reason for this is that it involves an artwork that at the moment is something of a secret and is related to the ‘Rembrandt year’ that the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is hosting to mark the 350 years since the artist’s death.

The story starts two and a half weeks ago. My colleague Caroline and I were at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. We had split our group of twenty-two pupils into two groups and were receiving a tour from two tour guides focussing on Dutch 17th century art. Such a tour inevitably stops off in front of Rembrandt’s Nightwatch. I was elsewhere in the museum with my group when Caroline was standing in front of Rembrandt’s massive masterwork.

While the group were answering questions Caroline noticed that the group was being very closely observed by another visitor. Moments later the same visitor came and introduced herself as Rineke Dijkstra, the Dutch art photographer who is perhaps best known for her photographs of teenagers, awkwardly posing before the camera on apparently empty beaches.

Dijkstra didn’t waste anytime in getting to the point, she had been commissioned by the Rijksmuseum to produce a new video work as part of the current Rembrandt year. It was going to be along the lines of the earlier work shot in Liverpool of British children talking and reflecting on a Picasso painting without the painting itself ever coming in shot. The new project was going to have its focus on Rembrandt’s Nightwatch though……and the bottom line was, that she wanted to use Caroline’s group of pupils as a part of the project.

Two weeks of organisation followed, permission from school to participate, permission from parents because the group was mainly made up of sixteen and seventeen year olds and the willingness fo the pupils themselves to be involved.

Two and a half weeks later we find ourselves, after museum closing time in the essentially deserted gallery of honour, with its collection of Vermeer, Steen, Hals and Rembrandt works. But in front of the Nightwatch a temporary studio has been errected for the film shoot. A white cube, bright lights and multiple cameras. It begins, I think, to dawn on the pupils that this is actually really quite a big deal! We are introduced to Rineke, she also seems quite excited about the work to be done that evening.

One of the Rijksmuseum tour guides take the girls off on a quick tour of some of the other paintings to settle nerves (yes, only girls, clearly a factor that made the artist pick Caroline’s group from the masses a couple of weeks earlier). A clear embargo was placed on photographing the set or any of the activities around the shoot. No images were to find their way onto social media!

Then it was down to work. Rineke sellecting clusters of girls to join her on the set that had been created in such a way that the pupils were issolated against an intensely lit white background.

I stood, a little out of view. Behind three monitors streaming the input from the cameras, not unlike the multiscreen effect that I had seen before in the Liverpool work. However, unlike that work, where the children involved were presented in a row side by side, this time the artist seemed keen to experiment with different approaches and compositional devices. The girls were arranged sitting on a bench together, but with the bench lined up in such a way that it was angled towards the camera. The result being that the faces of the girls appeared almost stacked up behind one another, way more dynamic and perhaps more in keeping with the work of Rembrandt himself. The girls were encouraged to talk about what they saw, what they thought, no script, just spontaneous reaction.

Dijkstra also asked a group of the girls to look at the painting and draw from it in their sketch books. After much careful positioning and repositioning of the girls, and laughter and a little bemusement from the young subjects, Rineke gave the sign, cameras rolled, silence decended. The girls drew, they looked, they drew again. This time the shoot ran for a considerable time, in fact it seemed to go on and on. The concentration was palpable. Were these really the same chatty, and often enough, distracted children that we see in class at school?

The material that was recorded was fascinating to see, as was the process of work of Ms Dijkstra as she cast her critical eye over the detail of the framing of each of the cameras. One of the later shots that was made reminded me more of Rineke’s well known photographic work of teenagers on the beach and a certain discomfort that creeps through in those images. A row of girls took up position against the white backgroud, the Rijksmuseum guide, just out of shot started to talk them through the painting, an extensive and detailed monologue which went on for quite an extended period. The girls focussed on the image of the painting, following the guides descriptive speech. You saw their gaze move around the image. They remained standing and looking. After a while you saw an ocassional adjustment of balance, a dip in concentration, a momentary distraction. Suddenly you observe that ‘not completely relaxed’ mark that is present in so much of Dijkstra’s work. Simply by filming for just long enough that lapse in focus starts to show itself, both physically and mentally.

23 August 2019

At the time of writing we had no way of knowing how much, if any, of what was filmed would in the end be used in the film work. We’ve reached the point now though that there is a finished work that will shortly be unveiled in the Rijksmuseum. The presentation of the work Night Watching in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is a couple of weeks away and the group of girls and us, their teachers, have been invited to the preview at the beginning of September.

The display of the German expressive paintings from a century ago features many of the names that you might expect, Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, August Macke, Franz Marc and Max Pechstein are all to be found. The museum website documents the show well as does the second link here on Wikipedia:

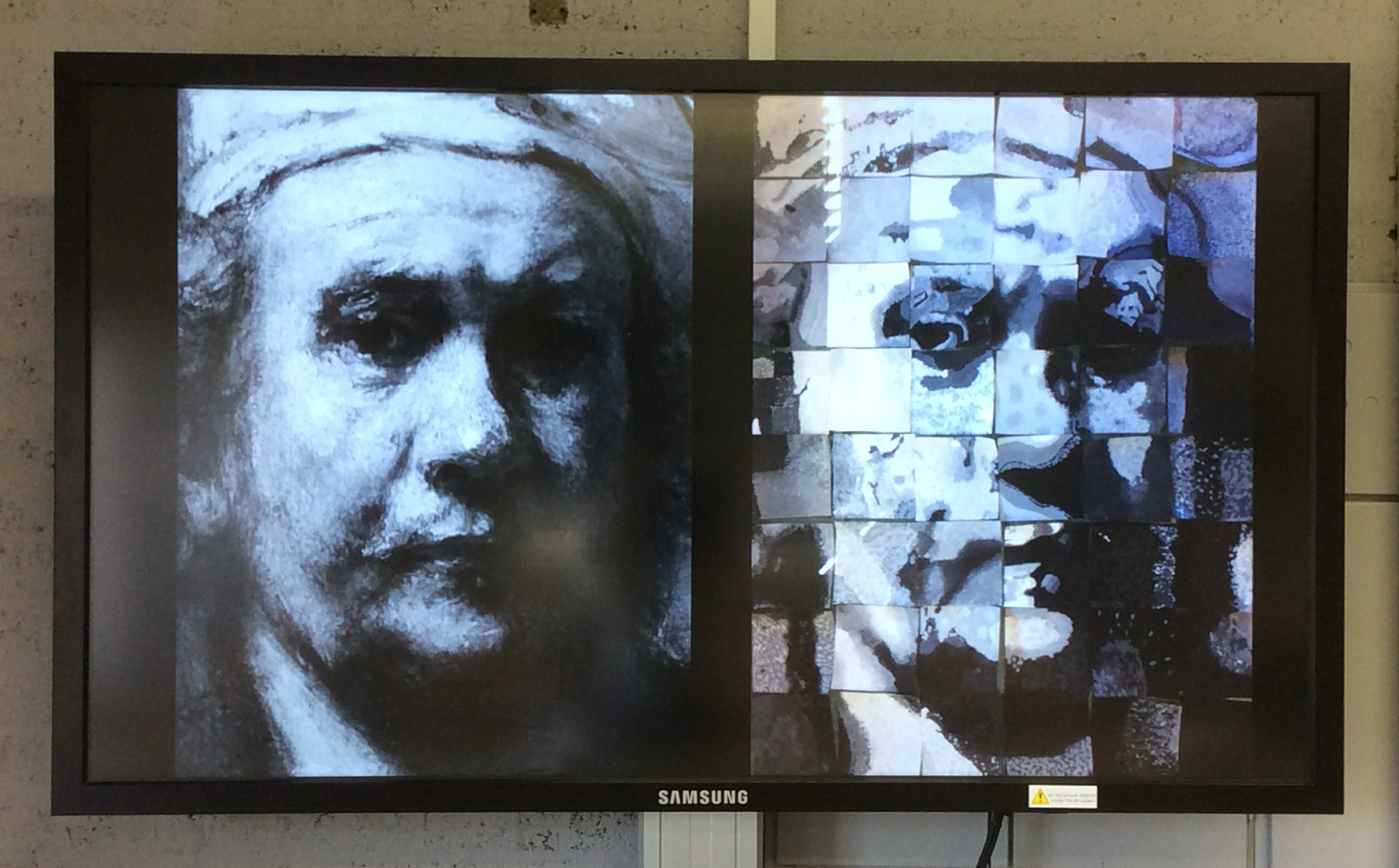

The display of the German expressive paintings from a century ago features many of the names that you might expect, Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, August Macke, Franz Marc and Max Pechstein are all to be found. The museum website documents the show well as does the second link here on Wikipedia: Some of the groupings are of rather kitsch hunting scenes, flower arrangements and the like. Perhaps the most engaging collections are the embroidered versions of icons from the worlds museum collections. Multiple versions of Rembrandt, Vermeer, Fragonard and Millet can all be found. It should be underlined just how many of these images that there are to see, spread across the museum walls in loose grid arrangements.

Some of the groupings are of rather kitsch hunting scenes, flower arrangements and the like. Perhaps the most engaging collections are the embroidered versions of icons from the worlds museum collections. Multiple versions of Rembrandt, Vermeer, Fragonard and Millet can all be found. It should be underlined just how many of these images that there are to see, spread across the museum walls in loose grid arrangements.

It is here that Scholte provides the twist, by displaying the reverse sides of the embroidery rather than the front sides. The variations and irregularities are fascinating to see. It is also here that a surprising parallel with the German expressionist work arises. These painters from the beginning of the twentieth century were interested in a looser and less self-conscious approach to there image making, less lethargic and more expressive. When you look at the reverse sides of the embroideries you are struck by the “unselfconscious” way many of them are made. This is of course hardly surprising when the makers’ attention has been so fully engaged with the other side of the image. Many of the resulting images have an extremely expressive quality as abundances of loose threads cross cross one another leaving an often chaotic, reversed and yet recognizable end result.

It is here that Scholte provides the twist, by displaying the reverse sides of the embroidery rather than the front sides. The variations and irregularities are fascinating to see. It is also here that a surprising parallel with the German expressionist work arises. These painters from the beginning of the twentieth century were interested in a looser and less self-conscious approach to there image making, less lethargic and more expressive. When you look at the reverse sides of the embroideries you are struck by the “unselfconscious” way many of them are made. This is of course hardly surprising when the makers’ attention has been so fully engaged with the other side of the image. Many of the resulting images have an extremely expressive quality as abundances of loose threads cross cross one another leaving an often chaotic, reversed and yet recognizable end result.