© Maurizio Anzeri, Rebecca, 2009

© Maurizio Anzeri, Rebecca, 2009

© Maurizio Anzeri, Rita, 2011

© Maurizio Anzeri, Rita, 2011

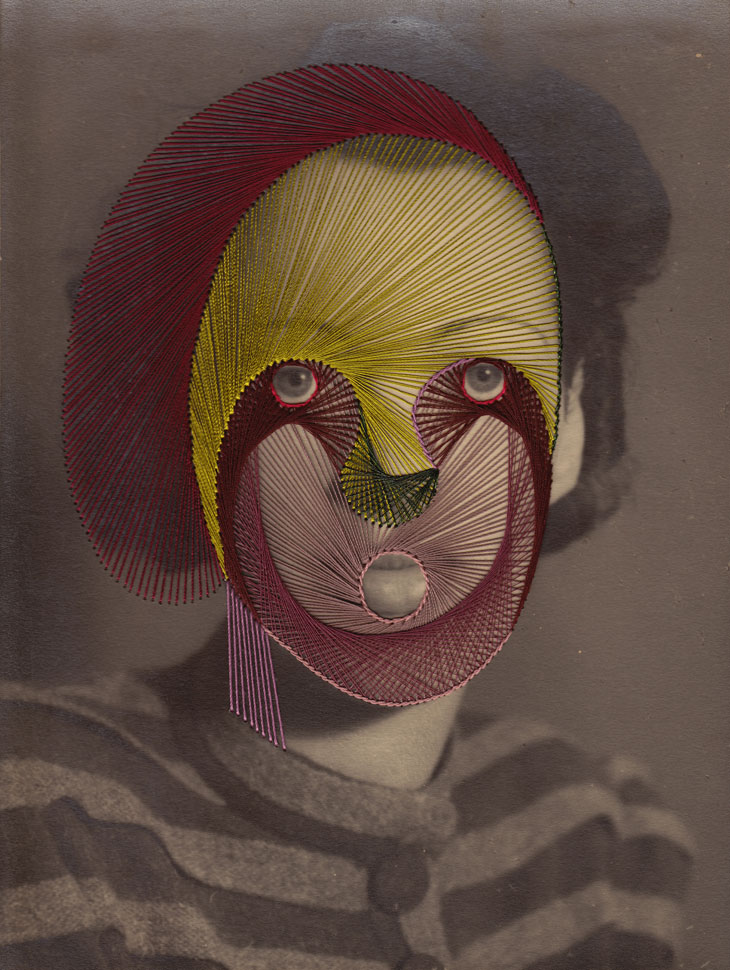

I came across Maurizio’s work through an unusual root – Bric-à-brac -, a section of the electronic journal Sans Soleil, specialized in issues related to Art Brut and self-taught art. Not only because of that but also (1) because embroidery is a very common medium within the world of art brut, and (2) because it is also fairly common to encounter appropriations of portraits that authors then re-work – in a sort of manifestation of the complexity of any identity notion or even as a symbolic expression of transcendental ego features -, I “was lead” to believe that Maurizio was not an academically trained artist, nor was he in a conventional circuit.

Anyway, my instinctual mode of association came into place and I found myself thinking of spontaneous art. It was only when I looked for more of Maurizio’s work on the internet that I realized it was framed in a completely different world, though that didn’t change the fact that I really enjoy his embroidery work. The problems that arose have little to do with the work itself, instead they pertain to the artist and the machine around him, which he is undoubtedly responsible for. There’s no sign of bad faith in Maurizio’s statement about his work. In fact, he meets my expectations, in part created by the qualities of the work itself, and speaks of something alike affective labor: “I work with sewing, embroidery and drawing to explore the essence of signs in their physical manifestation. I take inspiration from my own personal experience and observation of how, in other cultures, bodies themselves are treated as living graphic symbols. I then use sewing and embroidery in a further attempt to re-signify, and mark the space with a man-made sign, a trace. The intimate human action of embroidery is a ritual of making and reshaping stories and history of these people. I am interested in the relation between intimacy and the outer world.”

There is no denying that his work is sculptural. I don’t understand the need to label it as photographic, since the photographs are either found, archival or collected in flea markets and the medium that defines his artistry is embroidery, not photography. While googling for his work I came across a description in Vitrine Gallery where it says that Maurizio invent[ed] the term: ‘photo-sculpture’ and I can’t help but laugh. I don’t know who’s responsible for this slip or if this is just bad marketing, but it doesn’t help him in anyway to “sell” him as a surrealist or an avant-garde artist from the 70’s, especially because he was born in Italy in 1969 which would lead to biographic discrepancies.

© Maurizio Anzeri, Zelda, 2009

© Maurizio Anzeri, Zelda, 2009

© Maurizio Anzeri, A stitch in time… La Famiglia, 2013

© Maurizio Anzeri, A stitch in time… La Famiglia, 2013

Tri-dimensional photography, collages, photo-montages and so on, are part of the history of contemporary photography. With surrealism, dadaism and constructivism these techniques were already building their one symbolic field but with the advent of digital photography there was a new boom. The nostalgia, nothingness and apathy that led artists to turn to archives (not only but also) as a way to react to digital manipulation and bring back analogue deconstruction of the one-layered idea that photography is an amalgamate of signs that “were really there”, also sprouted the discussion about the photographic support and its potential to be something else.

Questions about what defines one’s identity in the 21st century merged with questions about what defines the photographic medium and with it portraiture gained a new light. There are several examples of collages, montages and embroidered portraits, most of them recognized and awarded in the last few years and I’ve been posting some of them here – an example is Julie Cockburn. This is the ground Maurizio walks on. There is not a single problem with not having invented the wheel. This lack of originality doesn’t define the work in absolute, only in relation to its culture. In an intimate relation, the work is free to become whatever one needs it to be. The problem is with lying and bad faith, which ruins expectations of an authentic creation.

Sean O’Hagan, from the Guardian, states Anzeri creates something new and surprising by applying an old-fashioned craft to old-fashioned artefacts. I keep questioning the need to adjectivize this as new, specially since the works-of-art are good enough on their own without the help of ‘new-technological’ or ‘ground-breaking’ add. There are also other descriptions which, without being false, are just over embellished – there are far too many adjectives and no critic of the art on display. It’s part of the problem with art criticism in general, too complex, so let’s see another example.

© Maurizio Anzeri, Round Midnight, 2009

© Maurizio Anzeri, Round Midnight, 2009

I can’t say who worte it, for there is no signature, but in Maurizio’s portfolio in The Saatchi Gallery one can read that Anzeri’s delicately stitched veil recasts the figure with an uncomfortable modesty, overlaying a past generation’s cross-cultural anxieties with an allusion to our own. My problem with this sort of statement is that it is pretentious and naïf at the same time: it is arrogant to the point that it suggests that what the work communicates should be contained (within a subject and its culture); and it is ingenuous in the sense that it presupposes that there is one understanding for the notion of ‘cross-cultural anxieties’, which means the spectator bust be either the colonizer or the colonized.

I’ll finish with another of Maurizio’s statement, since they are the most honest to his work: “I’ve been collecting old photographs for a long time. A few years ago I was doing ink drawings with them and out of curiosity I stitched into one. I work a lot with threads and hand stitching, and the link to photography was a natural progression. I put tracing paper over the photo and draw on the face until it develops. Sometimes the image comes straight away, suggested by a detail on a dress or in the background, but with the majority of them I spend a lot of time drawing. Once the drawing is done, I pierce the photo with a set of needle-like tools I invented and take the paper away; the holes are obsessively paced at the same distance to convey an idea of geometry. When I begin the stitching something else happens, drawing will never do what thread will – the light changes, and at some points you can lose the face, and at others you can still see under it.”

text by Sofia Silva

One thought on “٠ Maurizio Anzeri and the problem with labelling and expectations ٠”