ArtSeen

Bernd and Hilla Becher

On View

Metropolitan Museum Of ArtBernd and Hilla Becher

July 15 – November 6, 2022

New York

In mid-July, a beautiful, monographic exhibition of the photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The show is accompanied by an impeccable publication, printed by Trifolio srl with essays by Jeff L. Rosenheim (the curator of the exhibition), Virginia Heckert, Gabriele Conrath-Scholl, and Lucy Sante. The catalogue concludes with an illuminating conversation between Rosenheim and the artist Max Becher about his parents’ life and work.

The Bechers’s photographs are crisp, four-square images of industrial subjects typically arranged in grids containing up to thirty images. The Bechers’s work emerged in the late sixties and is commonly associated with Minimal and Conceptual art. (Sculptures by their friends Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre are included in the show.) The Bechers’s studio near Düsseldorf, Germany was their base for photographic expeditions to Germany, Belgium, France and Great Britain, and they also maintained a small loft in New York for trips in the eastern United States and Canada. From the early seventies to the 2000s they regularly exhibited at Galerie Konrad Fischer in Düsseldorf and at Sonnabend Gallery in New York and participated in numerous solo and group exhibitions worldwide. Bernd died in 2007 and Hilla in 2015, and this elegiac exhibition provides a panoramic look at their achievements. Bernd and Hilla Becher is a love story that spans five decades as they pursued a singular photographic dream.

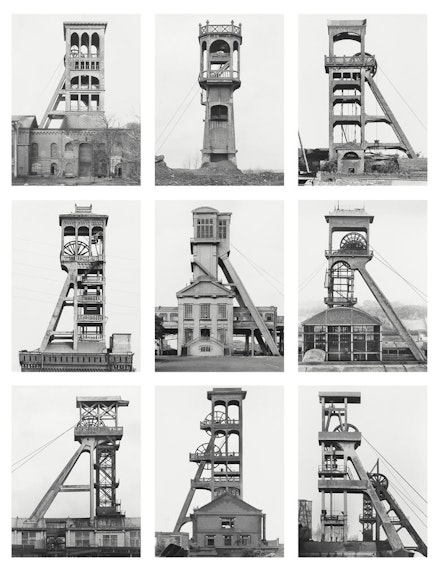

The Bechers are celebrated for rigorous photographs of subjects they called “technical constructions”: houses, winding towers, coal breakers, water towers, gas tanks, cooling towers, grain elevators, gravel plants, coal tipples, lime kilns, chemical plants, and sprawling industrial complexes. They preferred to photograph under what Kodak calls “cloudy bright” conditions that tend to soften shadows, crisply defining every rivet and girder on their subject. Invariably they framed their photographs so that they include a tiny bit of earth to establish context and scale. Beginning in the seventies , they exhibited arrays of photographs generally grouped by similar function: fifteen water towers, six lime kilns, four cooling towers, and so on. They termed these collections of prints “typologies.”

Twelve spectacular typologies hang in the spacious Menschel Hall at the Met. These impressive arrays are the Bechers’s signal works: if you are even mildly interested in contemporary photography, you likely know the typologies. Across the hall in six connected rooms, the remainder of the exhibition tracks their work from the fifties to the 2000s. If the typologies are their masterworks, it came as a revelation to see a room of “documentary” photographs the Bechers made in the precinct of the sprawling Concordia Mine in the Ruhr Region of Germany in the late sixties . Every aspect of the mine was photographed, including a startling panorama of the complex taken from a slag mountain. Other mines were also documented and published, but, like the Concordia project, they are exhibited with less frequency than the canonical typologies. I wondered if the dictates of contemporary art—signature style, easy to comprehend projects—suppressed awareness of the more traditional, documentary activities.

The Bechers wrote of making photographic records so precise that the buildings photographed could be reconstructed after they were demolished. Already in the late fifties they knew their time was limited; the functional architecture they selected (apart from houses) had a very short half-life. Heavy industry in the developed world was shutting down and moving east. On a trip to Asia, Hilla recognized a steel mill they photographed years before, reassembled in China. As the iron and steam age gave way to the atomic age, the urge to document these earlier industrial byways became acute. In 1948, Sigfried Giedion’s magisterial Mechanization Takes Command surveyed the anonymous history of the industries the Bechers would soon document. Walker Evans in “Before They Disappear,” a 1956 Fortune Magazine photographic essay, considered the demise of freight car insignias. And Evans’s young protégé, David Plowden, published Farewell to Steam in 1965, followed by photography books on Becher-like subjects: steam locomotives, barns, bridges, and tugboats.

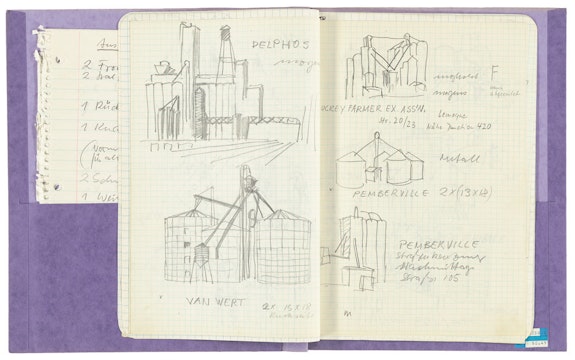

In a fascinating back gallery, we see an “unwinding” of the origins of the Bechers’s work, to borrow their term for a 360-degree photographic view of a subject. A selection of Bernd’s early drawings and photo collages of mines hints that he supplied the subjects they would seek out once they began working together in the late fifties . Hung adjacent to Bernd’s work, Hilla’s formidable early commercial photographs of natural objects suggest that she brought photographic craft to their collaboration. Quickly however, they each began to work both sides of the equation—Hilla found new subjects and Bernd spent time in the darkroom.

In the sixties a slew of black and white photographic papers was available, all with differing surfaces and tonalities ranging from textured to lustrous, glossy to matte, warm to cool. The Bechers printed their work on Agfa Portriga Rapid, a glossy, photographic paper whose dark tones toggled between reddish and greenish brown. (When this was discontinued, they found a replacement in Ilford “Warmtone” paper.) These warm print colors perfectly suited their gritty industrial subjects and nodded toward the reddish browns of their beloved nineteenth century photographic progenitors. In the catalogue, Trifolio approximates the print color with a mix of warm and neutral black inks.

In the sixties the Bechers worked in advertising and commercial photography to support their photographic projects. Like many artists, they picked up tricks from the commercial world that could be used selectively in their work. The most significant device they adapted from commerce was a propensity for strong, graphic representations of their subjects. They spoke of showing a structure’s best side, as if they were portraitists—which, in a sense, they were. When they pointed their cameras at blast furnaces or cooling towers, they sought strong pictorial gestalts. Bernd studied typography: two grids of coal winding towers included here reminded me of type specimen books.

As I considered the Bechers’s work in advertising, I googled the New York ad agency DDB’s Volkswagen ads from the sixties . A 1963 ad popped up, a 3 by 5 grid of fifteen identical VW “Bugs” with the witty tagline, “The Volkswagen Idea of Evolution.” (That is, they never change.) The copy underneath offered an important qualification. Volkswagens never change “for the sake of change, only to make it better.” In a similar fashion, the Bechers’s photographs look monolithic once they hit on their structured typologies, but the show reveals a subtle evolution. Like the incremental improvement of the “Bug,” the Bechers tinkered with their arrays to arrive at the mature typologies on view in the Menschel Galleries.

Despite their preservationist drive, I think it would be a mistake to see the Bechers’s passion as simply an archival one. As a photographer I see the pleasure they took in their work. I can imagine the excitement they felt each time they found a suitable subject and the joy that followed as they planted the sturdy tripod and set up their camera. Balanced against the multiple satisfactions of photographing in the field, the pleasures of working in the darkroom, on the “wet” side, were equally delectable. There are few more satisfying moments than confirming a negative you spent hours preparing to expose was perfectly exposed and processed. Or the pleasure of opening the foil envelope of photographic paper and inhaling the sweet scent of the gelatin emulsion. Or, in taking a moment to admire the high gloss surface of your warm print as it comes off the heated ferrotype drum. Once the prints were made, joy continued administratively as you arranged and rearranged grids of images, sequenced books, hung exhibitions.

During a scholar conference before the show opened, the question of humor in the Bechers’s work was raised. Like that of the 1963 Volkswagen ad, the Bechers’s humor could be very dry indeed. Obvious examples of their wit can be read in the early “Framework House” photographs. These eccentric homes are themselves sight gags with dark timbers set into white stucco walls at crazy kat angles. The framework houses were always photographed from the gable end and this flat, schematic view produced an almost childlike legibility: “See mommy, this is what a house looks like!” An obvious joke is found in one of the earliest typologies, the diptych Framework Houses, Germany, 1960–72. A large gabled view of a wood frame house occupies the left side of the work. On the right, nine smaller prints of similar houses are arranged in a 3 by 3 grid. The imagined punchline is that the mother house on the left produced these nine baby houses. It’s not surprising then to read in Gabriele Conrath-Scholl’s catalogue essay that the Bechers produced witty photomontages for the 1964 International Toy Fair.

The Bechers’s sensitivity to the perils of extinction reminds me of bird watchers. Like serious birders, they were always on the lookout for fresh industrial specimens and when they saw one, they would carefully note the location and return later to photograph it. A marvelous vitrine contains some of their notebooks that record these discoveries in pencil sketches. On my first visit to the show, I passed through the prints and drawings galleries on the way to the Becher show. I’ve noticed that the prints and drawings on display sometimes anticipate material in the changing shows just beyond. And, sure enough, before you enter the Becher show, there’s a small selection of bird imagery ranging from the seventeenth century to the present as if to prepare you for the two birders extraordinaire around the bend.

The 1970 Information show at MoMA was the first time I saw the Bechers’s photographs. Their contribution to the catalogue (recently reprinted on the fiftieth anniversary) was a photograph of a gas tank elliptically titled “Anonymous Sculpture.” This curious term would be the title of their first book, Anonyme Skulpturen: A Typology of Technical Constructions published later that year. The work hanging in Information consisted of a grid of thirty cooling towers. I wondered why the Bechers hadn’t reproduced a cooling tower in the catalogue. Could it be that no one knew the purpose of a cooling tower, whereas gas tanks were totally ubiquitous? For all the formality of the Bechers’s work we have seen how it could engage different modalities and meanings—portraiture, graphic design, preservation, humor. Perhaps the decision regarding what to exhibit was made last minute after the catalogue went to press. Might they have chosen cooling towers instead of gas tanks because the function of a cooling tower obliquely addressed the heated conversations taking place at that time in New York and across the country? This was, after all, the moment of the tumultuous Art Strike, the Kent State Shootings—which took place in May 1970, one month before Information opened—and growing calls for the end of the war in Vietnam.

In 1973 I met Hilla when she visited John Baldessari’s Post Studio Art Class at Cal Arts. She spoke about the work she was making with her husband and emphasized its connection to the classifying systems developed in the sciences. She described how they organized photographs of anonymous structures according to function and presented them in grids to emphasize these visual similarities. After Hilla’s talk, Baldessari asked me if I could drive her back to her motel in West Los Angeles. As we neared the motel, Hilla asked me if I could take her to Long Beach to scout oil wells the next day. Because of gas rationing, I didn’t have enough fuel, and I gave her the name of someone who had gas. Later I heard from Baldessari that Hilla decided against photographing oil wells.

I was in Los Angeles a few weeks ago, and on the way to the airport the taxi passed the Inglewood Oil Field, a continuation of the petroleum deposit in Long Beach that Hilla wanted to visit. I looked at the “nodding donkey” pumpjacks and at the tank farms scattered across rolling, dusty hills. I could see how oil derricks and storage tanks would interest the Bechers. As the taxi continued toward the airport, I realized that oil wells wouldn’t fit the structure of the typologies. Like high tension electrical pylons, another abandoned subject, photographs of oil pumps would allow too much of the earth into the viewfinder. In the classic typologies, industry, in all its forms, eclipses the landscape. The minimization of site allowed for the industrial subjects, photographed in far flung locations and under different conditions, all to have visual parity and weight. On top of this disqualifying formal gestalt, the blinding Los Angeles sun, so treasured by generations of California photographers, would likely prove an insurmountable challenge for this couple whose idea of happiness was photographing on cloudy days.