ArtSeen

Strategic Vandalism: The Legacy of Asger Jorn's Modification Paintings

On View

PetzelMarch 5 – April 13, 2019

New York

In the pit of the post-war Modern European Theater lay the ruins of the School of Paris. Its various painterly edifices, a formerly fruitful mélange of Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism had been shaken loose from their avant garde foundations by cataclysmic world events. This pit would, in part, become dominated by an aesthetic pendulum swinging between the capriciously whimsical and the patently absurd—between the promise of revived joy and the depressing reality of modern alienation. Riding such a pendulum, like apocalyptic jockeys, were the likes of Danish painter Asger Jorn.

Jorn was a founding member of COBRA—a loose coalition of painters taking their name from the initials of their respective cities of origin (Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam)—who were interested in cultivating a neo-expressionism characterized by an ingenuous naiveté and a brut figurative bent. Jorn was also a primary backer and participant in the Marxist, post-Surrealist Situationist International (SI). The COBRA painters, which included Alex Jawalensky and Karel Appel, channeled the vital whimsy of children's drawings expressed in high-key slashing color, while Situationists were preoccupied with reacting to and critiquing the political and cultural absurdities of the Marshall Plan's economic and social reformation of post-World War Two Europe. This influx of capital from the United States effected an acceleration of American-type commodity fetishism in post-war Europe. Raoul Vaneigem, an important theorist of the SI, believed the loss of creative whim in contemporary life was largely the fault of postwar development, the proliferation of advertising comprising capitalist consumerist spectacle. In the ironically titled chapter "The Age of Happiness," in his 1967 SI treatise The Revolution of Everyday Life, he wrote: "The face of happiness vanished from art and literature as it began to be reproduced along endless walls and hoardings, offering to each particular passerby the universal image in which he is invited to recognize himself." This threshold of disenchantment brought on by a wave of simulated joy in the perpetual advent of hyped consumerist promise was one that the Situationists would purposely trespass.

Following Vaneigem's diagnosis, Jorn sought to assault the shallow imagery of capitalist spectacle, reinvigorating painting with a ludic rascality intended to disarm and reimagine its tradition with radical importance. However, his approach was seen as transgressive within the excoriating dictates of the SI, which eschewed painting altogether as an eminently disposable, bourgeois affectation. Jorn's position as COBRA and SI member was thus a complex one, and his art constituted a double transgression. These facts imbue Petzel Gallery's Strategic Vandalism: The Legacy of Asger Jorn's Modification Paintings, an exhibition of work by Jorn and the artists who prefigured or followed him, with a sense of radical irresolution. The "strategic vandalism" of the show's title refers to the SI tactic of détournement—hijacking a preexisting image to counter its previous meaning—however, Jorn and many of the other artists involved in the show do something more nuanced: In building upon or changing extant images, they also pay homage, albeit in a playfully sardonic way, to painting's traditional capacity to serve as a useful medium of cultural commentary and critique.

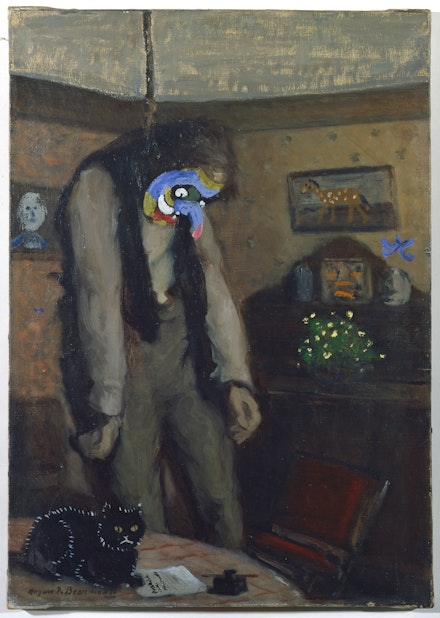

A selection from Jorn's "Modification" painting series (1959–1963) inaugurates the show with a nod to the artist's contested status. These demonstrate how his adaptions of kitsch were, in the words of curators Axel Heil and Roberto Ohrt, "examples of the Situationist International technique of détournement and a critique of it." The complex fold of such a double-acting aesthetic, Jorn's cagey sophistication, is carefully examined by the curators who refuse to make simple binary correlations between Jorn's disfigurement of and appreciation for his "originals." Heil and Ohrt avoid a facile before/after or faced/defaced approach in favor of showing Jorn as an artist who both mocked the appropriated images—for the most part, generic landscapes and portraiture—as banal dreck, while ironically also reimagining them as modes of painterly transport via his benevolent "vandalism."

Jorn lusciously delivers his acts of vandalism on an expressionist, painterly platter. In Brotherhood Above All (Fraternité avant tout) (1962), a 19th century double portrait of siblings is painted with a semi-opaque white that distorts the sitters' limbs to make them more active, as in a childish depiction of the self. One sibling has a blond beard painted on while the other features a spatter of red. In the background, a Miró-like, abstraction intervenes between the two. The painting's brash disfigurations conjure childish transgressions and their potential subconscious reasoning. There is something profoundly Freudian in the violent, Oedipal reaction that Jorn pictorializes here, yet the work seems to escape the tragic portent of that classic narrative. It's a seriously comic combine.

The found kitsch village landscape of The Little Grey Home in the West (Modification) (1959) is of much darker portent, overpainted as it is with two black "clouds" that dwarf the titular homestead. One resembles an atomic bomb mushroom cloud, while the other forms a dark personage come to menace the ostensibly calm and peaceful scene. It is almost a direct allegory of the destructive toll that World War Two and its Cold War aftermath took on the psyche of parochial sensibilities in pre-war Europe. The poles of nuclear annihilation and psychic Armageddon crowd this quaint, tumbledown house as aggressively expressionist ellipses.

Enrico Baj, Per Kirkeby, and Francis Picabia, all represented in this rambling exhibition, develop and elaborate painterly gestures similar to Jorn's approach, by initiating new works with kitsch genre paintings or commercial advertisements. Baj is closest to Jorn in visceral feel, with the importation of crusty Art Brut golems into his appropriated images. In his combine painting The Whore with the Ultrabodies (1959), two obviously male, semi-abstract monsters menace an apparently unimpressed prostitute (some vintage porn) diffidently lighting up a cigarette. The passive object (the "original") is hilariously re-made as a resiliently hardcore identity, blithely resistant to the interrogative perversities lurking beneath the male softcore gaze. Kirkeby, in his late career known for a more lyrical and pastoral painterly vision, is represented by two modified thrift store landscapes that lend a more conceptual, ironic perspective to his life's work. Picabia is shown with a beer poster readymade entitled Bière Sarrator (ca. 1925), which depicts what appears to be a doughty, fur cap-wearing peasant from Alsace-Lorraine (the origin of the brewery) smoking a clay pipe underneath the brand name written in a ghostly script. Knowing Picabia's love for puns and double-entendres, one is tempted to playfully misread the artist's appropriated smoke signal. A possible play on words combining biere, phonetically similar to the English funerary "bier" and sarrator, which sounds close to the Spanish aserrador, can be read as the hermetic missive "beir sawyer"—a "funerary carpenter," or even, if one considers the past tense of "see" embedded in sawyer, "death, past-sight." It's the kind of semantic gymnastics seen in many of Duchamp's readymade titles, such as the roughly contemporary Fresh Widow (1920). One can only assume that Picabia's latter-day, like-minded iconoclasts in the SI would heartily approve of such a critical, if cryptic, détournement of the spectacle of common advertising.

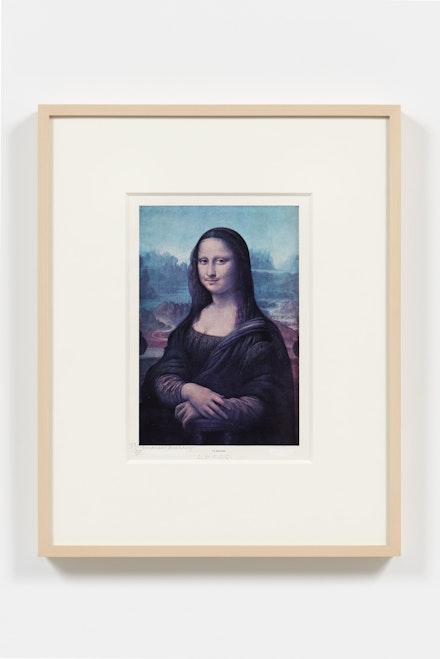

In the schoolboy-transgressive tradition of Marcel Duchamp—the prince of vandals?—represented here by a version of his mustachioed Mona Lisa, L.H.O.O.Q. (1919– 1964), are an ensemble of works from Mike Kelley's Reconstructed History (1989). Thought bubbles and obscene graffiti scratchings deface American Heritage-type images. In one, Alexander Hamilton amorously addressing George Washington ("kiss me") as Washington recoils ("ugh"), while another features a drawing of the Capitol rotunda as a pair of upturned breasts. Kelley's closing of the gap between Duchamp's drawing room-cleverness and his own sophomoric uncouth is one of the singular achievements of his unfortunately foreshortened career.

There is too wide a variety of different approaches to the alteration of given images here to adequately cover in this brief overview, but two more notable examples do merit singling out. Rachel Harrison shows a suite of drawings collectively entitled The Classics (2018), which seem to be digital prints of old art school sketchbooks of antiquities over which she has drawn multiple layers of neon-colored, expressionist lines. These appear attempts to literally re-trace art history, via liberated line work, obscuring classical figures with the same line exercises she may have used to memorialize their forms as a student. A more figurative overlay of art historical sources can be seen in Betty Tompkins's "Women Words" series (2017–2018), in which she blots out figures in classic works, such as a Velázquez's recumbent Venus or Vermeer's passive maid, with feminist-subjective, interpretive text. Both Harrison and Tompkins exemplify that there is much yet to elicit from the modification of inherited form and content. The willed sacrifice of painting on the altar of painting that Jorn promulgated proves a still vital ritual in the poetic re-description of both the whims of the received past and the absurdities of the given present.